Liberated Twice. The political rights of women 1918 | online exhibition - Instytut Pileckiego

Liberated Twice. The political rights of women 1918 | online exhibition

The Decree issued by the Chief of State on 28 November 1918, which granted women the right to vote and the right to stand for election, placed Poland amongst the most democratic and progressive European states.

In the fight for rights. Polish women under partitions

The fact that in the 19th century Poles did not have their own state left a distinctive impression on all aspects of their social and political lives. The Polish lands lacked the freedom necessary to attain economic and civilizational development. This had a considerable influence on both the situation of women, and the suffragette movement which developed in the second half of the century and strove to equate their rights with those of men. Access to education was one of the greatest challenges. There were no universities at all in the Prussian partition, while the authorities in the Russian partition did not permit to educate women at the Russified University of Warsaw. In autonomous Galicia, Polish women were allowed to study at the university – the Jagiellonian – since the 1890s, but only in one of two faculties: medicine or philosophy. Women were also discriminated against in civil law. The partitioning powers patterned their legal systems on the Napoleonic Code, which was in force in the majority of continental European states. Following the death of her husband, a Polish woman would not be entitled to independently bring up her own children and would have only a limited right to inherit; neither would she be able to certify contracts or wills. Basically, the Code made women subordinate to the authority of men in many spheres of life. The situation was worst in the Russian partition, where after the January Uprising (1863) women were punished along with their menfolk who had taken part in the fighting. Imprisonment, deportations, seizures of property and concomitant pauperization became the lot of thousands of Polish women. Political repressions and economic change caused the disproportions already existing between women and men to deepen.

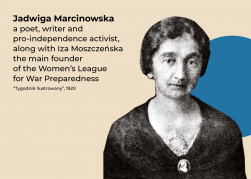

In the press, a discussion into the situation of women commenced in the 1870s. It was initiated by a group of Warsaw-based positivists, which included journalists and writers. Proposals were made to reform girls’ education and to admit women to universities, to develop vocational schooling, and also to remove the inequalities existing between women and men in civil law. Due to the fact that the Tsarist authorities failed to display any activity, Jadwiga Szczawińska-Dawid set up the first clandestine women’s college in Warsaw – the so-called Flying University. One of its students was Maria Skłodowska.

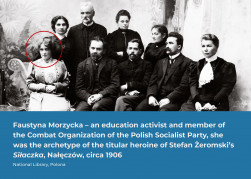

Despite these limitations, in the 19th century Polish women not only played the leading role in the patriotic education of children and youth, but also became active in public life. The 1890s witnessed the development of the suffragette milieu, which came to operate across all three partition zones, popularizing the slogan of equal rights and electoral rights for women. In due course, these circles established two important organizations: the Christian United Association of Landed Proprietresses and the progressive Union of Equal Rights for Polish Women. At the beginning of the 20th century a group of female Socialist pro-independence activists appeared amongst Józef Piłsudski’s close associates. These women went on to set up the Combat Organization of the Polish Socialist Party (PPS). All three milieus were to meet later, on the fronts of the First World War, while fighting for a free and independent Poland.

We want the whole of life! The feminists

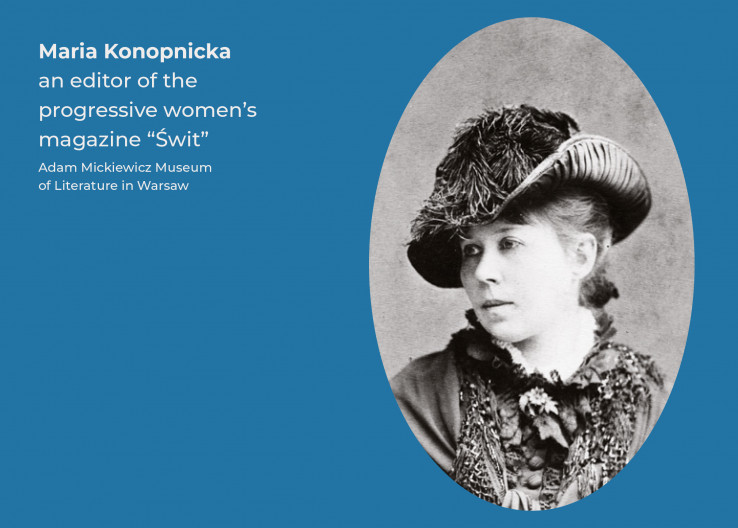

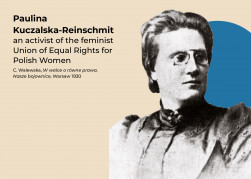

The founder of the Polish feminist movement was Paulina Kuczalska-Reinschmit, the co-creator and editor-in-chief of “Ster” (published in Lwów in the years 1895–1897, and in Warsaw from 1907), the press organ of the Union of Equal Rights for Polish Women.

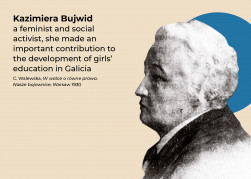

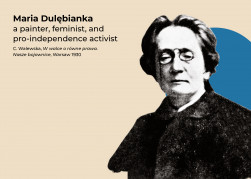

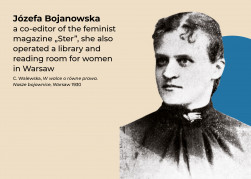

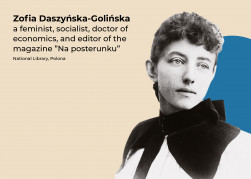

Regular contributors to the Warsaw-based “Ster” included the historians Helena Witkowska and Romualda Baudouin de Courtenay, the talented painter Maria Dulębianka, the social activist Józefa Bojanowska, the economist Zofia Daszyńska-Golińska, and the physician Justyna Budzińska-Tylicka. The educationalist, journalist and political activist Izabela Moszczeńska-Rzepecka wrote for the “Ster” on an on-and-off basis. At the same time in Kraków, Maria Turzyma published “Nowe Słowo”, which printed articles written by, among others, Teodora Męczkowska, a teacher of physics, and Kazimiera Bujwid, a laboratory technician and the collaborator and wife of the bacteriologist Odon Bujwid.

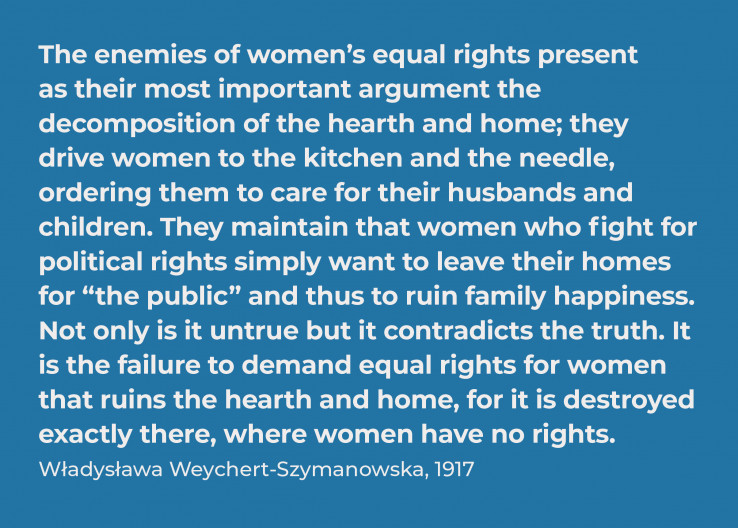

The feminist milieus used their journals to campaign for the equation of women’s and men’s rights, and disclosed instances of discrimination occurring within families, the sources of which were regulations taken from the ancient Napoleonic Code. These women demanded in particular the abolition of the humiliating provision according to which following the death of her husband a widow had to convene a family council or receive a legal guardian, which limited a mother’s power over her children. The Code also made it difficult to acquire citizenship and allowed women to take up employment solely with the consent of their husbands. Female journalists also conducted campaigns against double moral standards, and exposed the problem of prostitution and venereal diseases. They referred to mottoes of moral chastity, sexual abstinence before marriage, and marital fidelity.

The struggle for the electoral rights of Polish women was completely dependent on the will and decisions of the authorities of the partitioning states. Thus, although this postulate was not implemented, the feminists did achieve considerable success by bringing about the popularization of their slogans, which called for the equality of men and women, in the large cities. After 1911, the activists of the movement – increasingly disillusioned with legal ways of the struggle for their rights – started filtering through to the pro-independence milieus. Among others, they joined organizations such as the paramilitary “Strzelec”.

To do something useful. The Christian Democrats

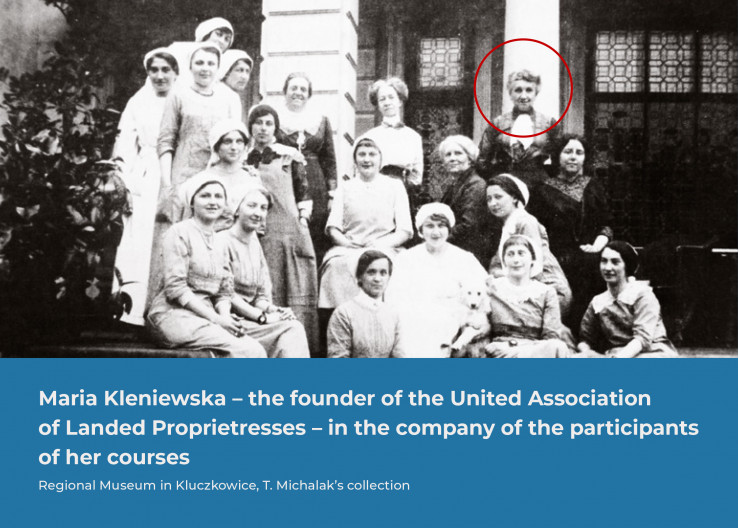

As opposed to developments in Western Europe, no Christian-Democrat party was established in the Polish lands. However, on the basis of social life there came into being a women’s association, the United Association of Landed Proprietresses (UALP), which based its program on the Catholic social teaching.

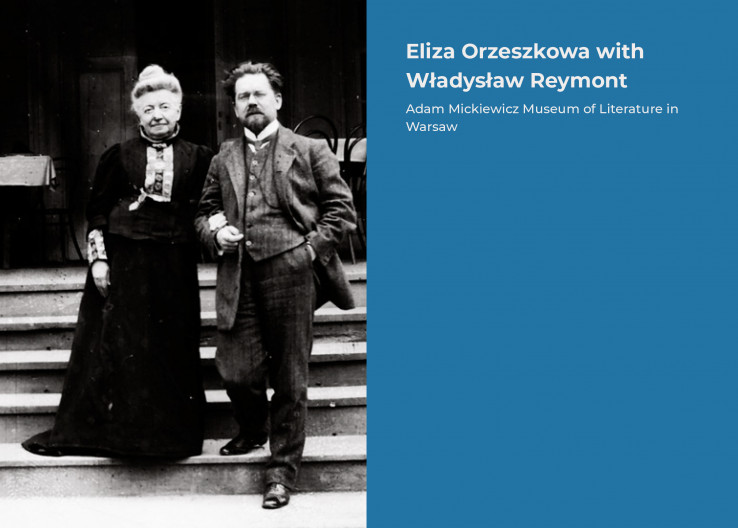

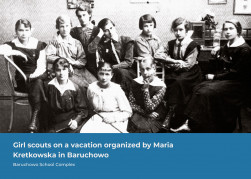

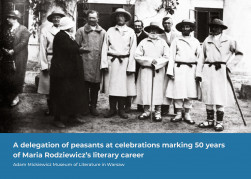

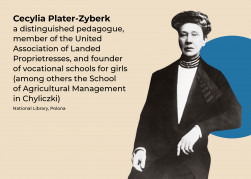

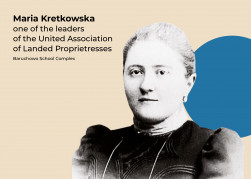

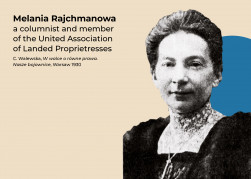

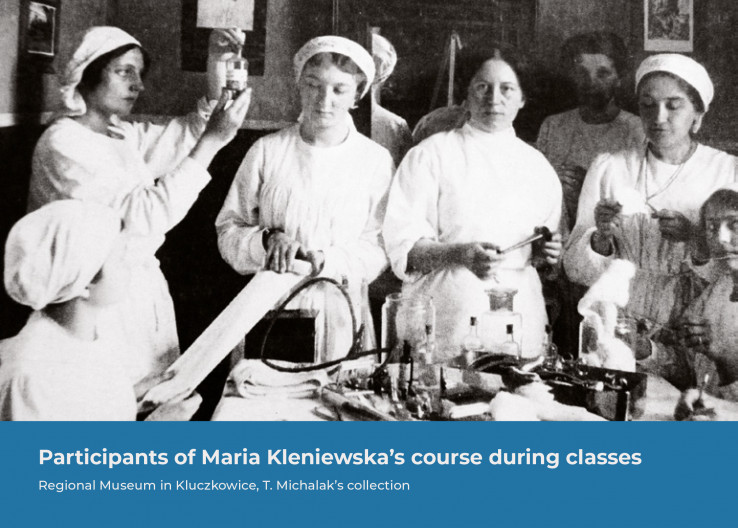

Maria Kleniewska of Kluczkowice founded the Association. Following the publication of the Rerum Novarum encyclical, she gathered a body of active women who originated – as she herself did – from the landed nobility. The leaders of the UALP were Maria Rodziewicz (a popular writer), Maria Kretkowska, Maria Karczewska and Irena Kosmowska; Eliza Orzeszkowa became an honorary member. They promoted a program of social solidarism which was intended to build bridges between the various social strata and to mitigate the effects of brutal capitalism.

The final quarter of the 19th century was marked by a rapid transformation of economy. One of its manifestations was mass migrations of people from rural areas to cities. Many country girls without any acquired profession worked as servants in private households. Their job was low-paid, and was beyond any form of legal protection. Since the profession of servant was inextricably tied with the notion of celibacy, in their old age these women frequently ended up in houses for the poor. Young girls were also exposed to sexual harassment in the residences of their employees.

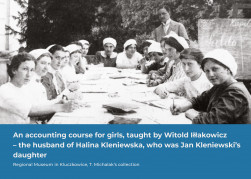

The activists of the UALP directed their assistance mainly to women and girls from the country. They brought midwives to villages, set up playgrounds for children, and taught the principles of child care and hygiene. They also opened vocational schools for girls, in which the teaching of cutting, sewing, weaving wicker baskets and nursing was supplemented with that of reading, writing and arithmetic. Other activities focused on establishing cooperatives and shops which offered local artisan products and produce. The members of the Association modeled themselves after the social activities of Br. Honorat Koźmiński, the creator of habitless female orders that engaged themselves with caring for working class children and women. The Christian Democrats considered that women should have the possibility of participating in elections in order to better discharge themselves of their civic duties. They propagated the concept of the complementarity of the sexes, calling for granting women access to education and the job market, and for removing from the Napoleonic Code provisions supporting female discrimination. After 1911, they gave fuller support to pro-independence activities and made a contribution to the rebirth of the Polish state.

Explosives under corsets. The revolutionaries

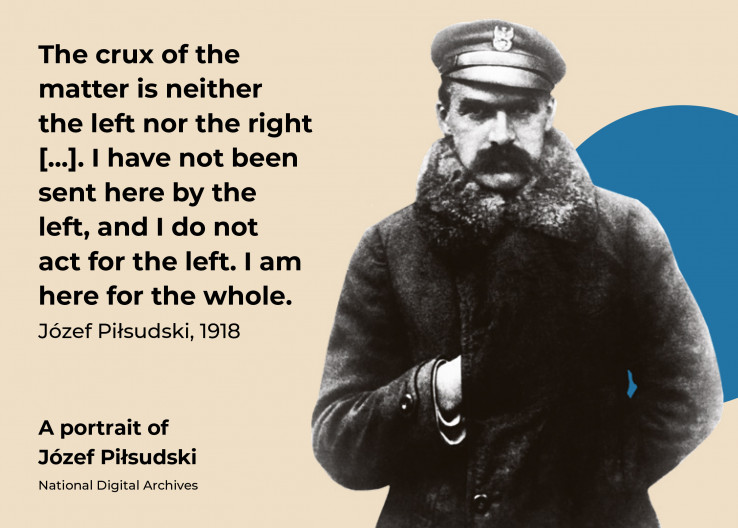

Following the events of 1905, women involved in the activities of the feminist Union of Equal Rights for Polish Women and the Christian-Democrat United Association of Landed Proprietresses chose to take the path of legalism. The pro-independence socialists took a different way. Namely, they joined the Combat Organization of the Polish Socialist Party, headed by Józef Piłsudski. They considered that women would gain equal rights only if Polish independence was won through an armed struggle. They became known as dromedaries or revolutionaries.

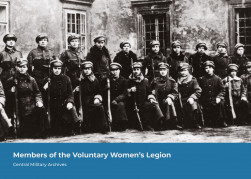

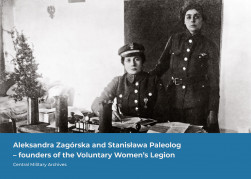

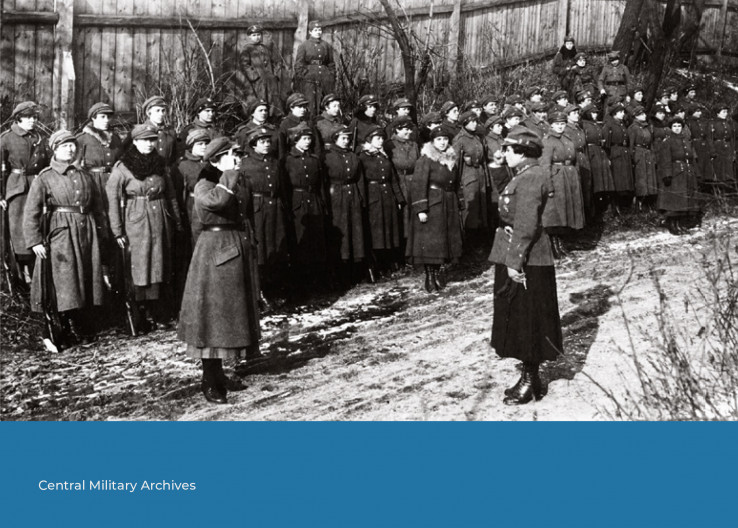

This trend was represented by, among others, Aleksandra Szczerbińska, Maria Owczarek, Hanna Paschalska, Józefa Rodziewicz, and Zofia Prauss. They considered the Tsarist autocracy and the Russian apparatus of political repression as the main source of oppression. And since they had been raised in the tradition that everything which was oppositionist and anti-Tsarist was revolutionary in nature, they called themselves “revolutionaries”. Piłsudski was unwavering in his attempt to transform the social revolution of 1905 into an armed national uprising. The women from the Combat Organization of the Polish Socialist Party (the “dromedaries”) engaged in pro-independence agitation in factories, and ferried ammunition and Mausers under their skirts to prearranged contact points. They would also hide explosives in their corsets. After 1911, this relatively small number of women managed to gather a larger group of activists around them: poets, translators, students and secondary-school pupils.

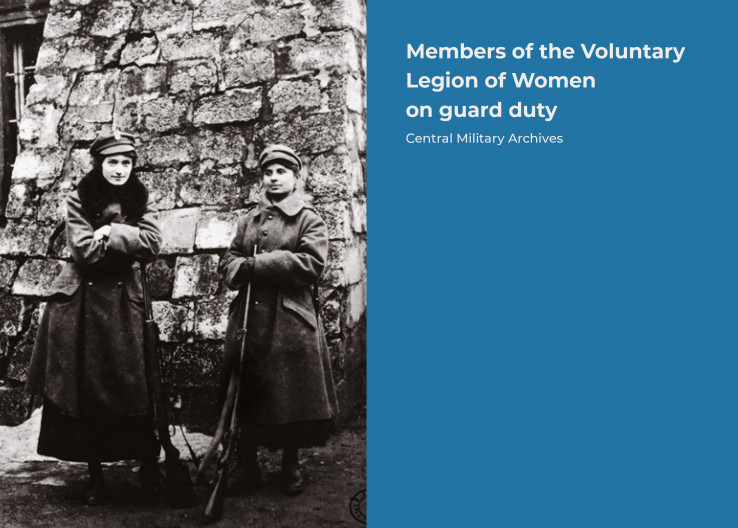

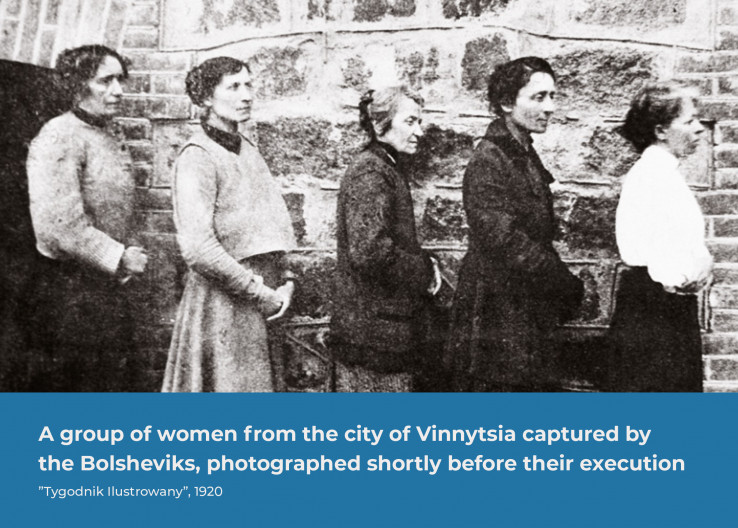

These women took part in terrorist activities targeting the Tsarist administrative structure; during the First World War – wearing male uniforms and under male pseudonyms, like e.g. Wanda Gertz – they fought as soldiers in the Legions. They also worked as intelligence operatives and provided aid as nurses. Frequently, the price they had to pay was high – imprisonment, torture, or even death.

The year 1918

Diplomatic and military efforts made Poland return in 1918 to the political map of the world. The gigantic endeavor of creating the structures of the Polish Republic on the lands recently divided into three partition zones meant, among others, taking many demanding administrative and political actions. This included organizing the first free and democratic elections to the Polish parliament.

In November 1918 there was a number of centers of political power in the Polish lands. The Regency Council in Warsaw, before it transferred authority to Józef Piłsudski, following his return from Magdeburg, had not intended to grant electoral rights to women. However, on 7 November the so-called Lublin Government, headed by Ignacy Daszyński, gave these rights to women.

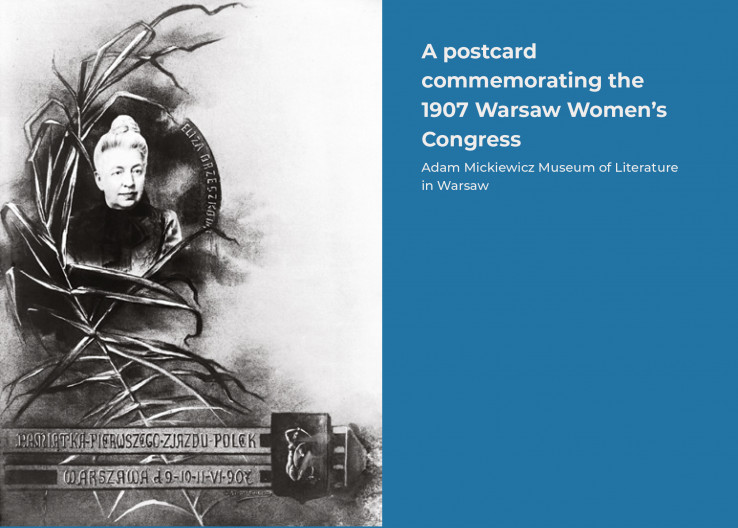

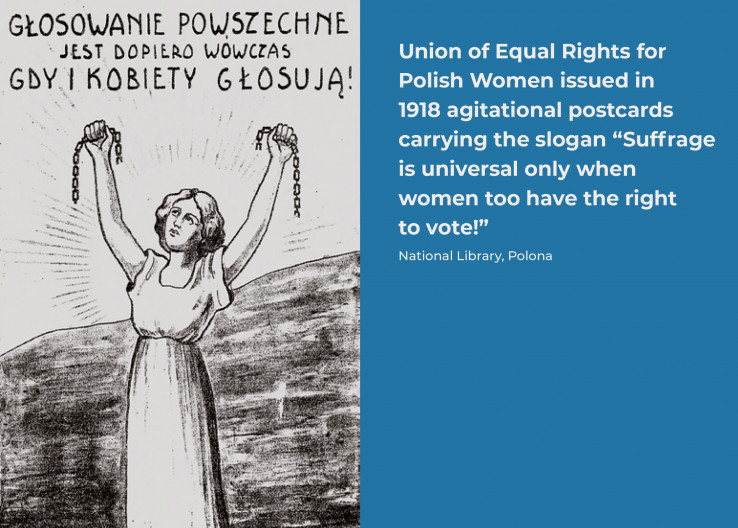

Against this backdrop, in September and November 1918 female political activists organized a number of rallies and conventions for women from all three partition zones under the banner of equal rights in a free Polish state. Various women’s organizations representing the landed nobility, the intelligentsia, Christian circles, and the socialists attended these events. At the time, the Union of Equal Rights for Polish Women issued agitational postcards carrying the slogan “Suffrage is universal only when women too have the right to vote!”. All active women’s milieus, with potential to reach and convince the leading politicians to the concept of equal rights, mobilized themselves.

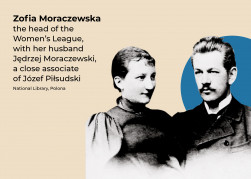

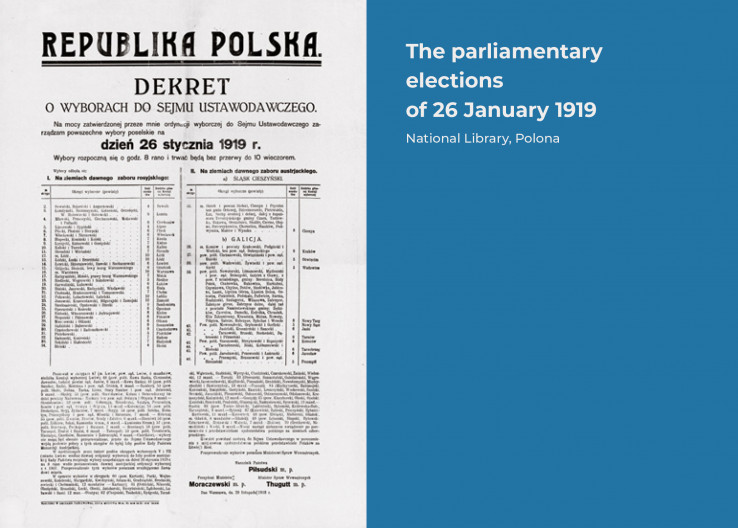

The Chief of State’s Decree on the Electoral Statute to the Legislative Parliament was published on 28 November. Every citizen of the state who was 21 years of age became an elector. Article 7 of the Decree provided that “Electors to the Parliament shall be all citizens of the state who are actively eligible to vote”. In the middle of winter 1919, Polish women went to the ballot boxes for the first time, as fully empowered citizens of the Second Republic. The following became the first female MPs in the history of the Polish parliamentarism: Gabriela Balicka, Jadwiga Dziubińska, Irena Kosmowska, Maria Moczydłowska, Zofia Moraczewska, Anna Piasecka, Zofia Sokolnicka, and Franciszka Wilczkowiak.

Disputes on emancipation

Despite the difficulties posed by the partitions and the lack of self-determination, the course of the process of women’s emancipation in the Polish lands was in many ways the same as in other countries. Similar issues were explored: the division of the social roles of women and men, civilizational challenges, access to education, profitable employment, and electoral rights. And, similarly, active Polish women became members of feminist and Christian-Democratic groupings.

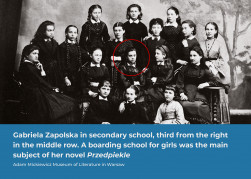

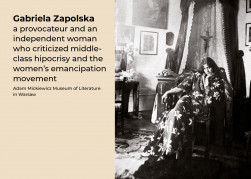

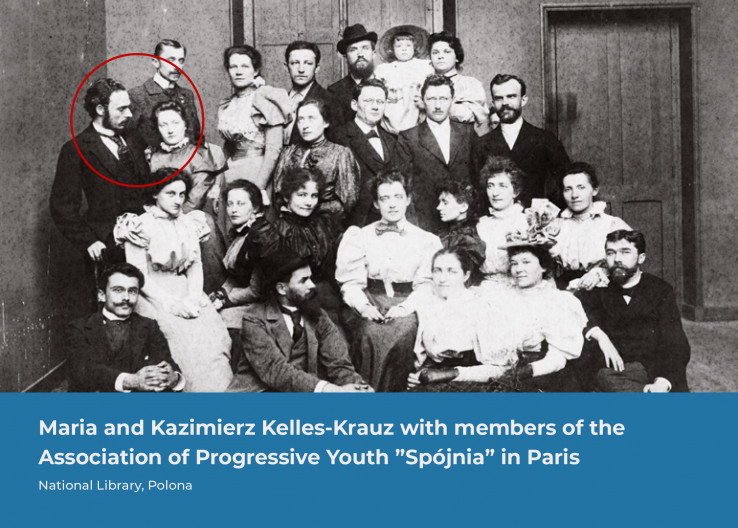

In their argumentation, both sides of the dispute on equal rights for women – one which lasted nearly fifty years – invoked different values: justice, equality, freedom. This found reflection in both journalism and literature. For socialists, the point of reference could be equality (Ignacy Daszyński), the aspiration to freedom (Kazimierz Kelles-Krauz), or to justice (Józef Piłsudski). The leader of the nationalist camp, Roman Dmowski, resisted the idea of equal rights, however other members of his grouping remained neutral or were even favorably disposed to the concept. It occurred that liberals would agree to the demand for equality under civil law, but would voice skepticism about electoral rights (Bolesław Prus). Some authors – such as Gabriela Zapolska, who in her plays masterfully laid bare double standards of morality and the harm done to simple women (The Morality of Mrs Dulska) – were opposed to the equality of rights. Catholic bishops feared emancipation, whereas parish priests and the religious supported the concept, basing their views on the Catholic social teaching and cooperating with the activists of the United Association of Landed Proprietresses.

That women were granted political rights in 1918 was the result of a great many causes. During the partitions Polish women were the primary carriers of the nation’s cultural code, which was handed down to successive generations. Women from the youngest age group, who fought on the fronts of the First World War, strove to gain the position of a causative factor in history. The slogan of the “heroic act”, introduced by Maria Dąbrowska during the war, also helped overcome the stigma of the failure of the January Uprising, which their grandmothers had witnessed or in which they had actively participated. The 1918 Decree expressed Piłsudski’s acknowledgement of women’s contribution to culture and society, and of their patriotic dedication during the war time. Thus, Poland’s return to the map of Europe became conjoined with the emergence of Polish female citizens who were aware of their rights.

"Liberated Twice. The political rights of women 1918” exhibition

Conception: Prof. Magdalena Gawin

Curatorial cooperation: Hanna Radziejowska

Biographical notes: Dr. Marcin Panecki

Production manager: Dr. Agnieszka Konik

Graphic design: zespół wespół, Beata Dejnarowicz

Translation: Maciej Zakrzewski

Digital adaptation: Krzysztof Pełka, Aleksandra Kiereta, Natalia Radulska

Acquisition of materials: Paulina Wiśniewska

Zobacz także

- Lemkin. Świadek wieku ludobójstwa | wystawa wirtualna

Wystawa wirtualna

Lemkin. Świadek wieku ludobójstwa | wystawa wirtualna

Czy ludobójstwo to domena historii? Co doprowadziło do powstania jednej z najważniejszych odpowiedzi intelektualnych na tragiczne doświadczenie II wojny światowej? Poznaj historię Rafała Lemkina - człowieka, który stworzył pojęcie ludobójstwa!

- Podwójnie Wolne. Prawa polityczne kobiet 1918 | wystawa wirtualna

Wystawa wirtualna

Podwójnie Wolne. Prawa polityczne kobiet 1918 | wystawa wirtualna

Przyznanie kobietom czynnych i biernych praw wyborczych na podstawie dekretu Naczelnika Państwa z 28 listopada 1918 roku stawiało Polskę w szeregu najbardziej demokratycznych i postępowych państw Europy.

- Paszporty życia | portal tematyczny

Wystawa wirtualna

Paszporty życia | portal tematyczny

Zapraszamy do odwiedzenia strony internetowej o działalności grupy polskich dyplomatów, którzy podczas II wojny światowej w szwajcarskim Bernie, we współpracy ze środowiskami żydowskimi ratowali żydów z całej Europy.

- Lemkin. Witness to the Age of Genocide | online exhibition

Wystawa wirtualna

Lemkin. Witness to the Age of Genocide | online exhibition

Is genocide a domain of history? What led to one of the most significant intellectual responses to the tragic experience of World War II? Explore the story of Raphael Lemkin – the author of the concept of genocide!

- Zawołani po imieniu | wystawa wirtualna

Wystawa wirtualna

Zawołani po imieniu | wystawa wirtualna

Kim są „Zawołani po imieniu”? To Polacy, którzy podczas okupacji niemieckiej zostali zamordowani przez Niemców za pomoc niesioną skazanym na Zagładę Żydom. Losy pomagających przez lata były znane tylko ich najbliższym.