Lemkin. Witness to the Age of Genocide | online exhibition - Instytut Pileckiego

Lemkin. Witness to the Age of Genocide | online exhibition

Is genocide a domain of history? What led to one of the most significant intellectual responses to the tragic experience of World War II? Explore the story of Raphael Lemkin – the author of the concept of genocide!

Chapter 1. Prologue

The crime of crimes

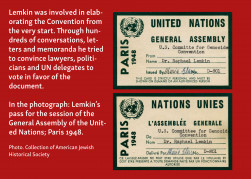

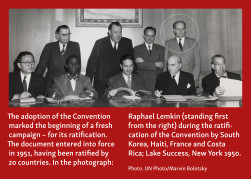

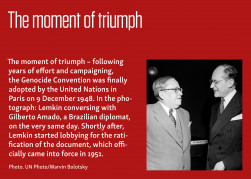

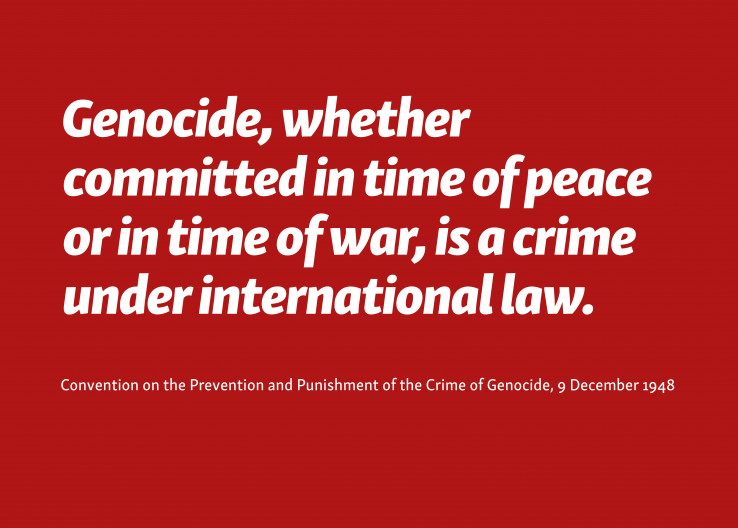

On 9 December 1948, the United Nations unanimously adopted the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. All acts committed “with the intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group” became a crime under international law. This was a natural consequence of the tragic experience of the Second World War: pursuant to the Convention, the perpetrators of genocide would be punished and the crime itself prevented from being repeated.

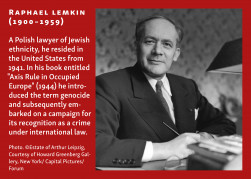

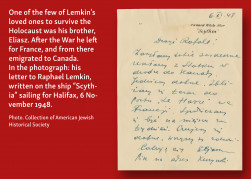

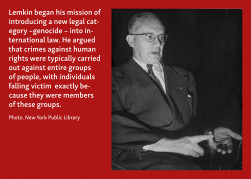

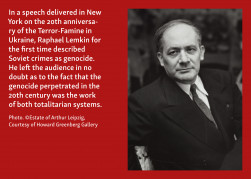

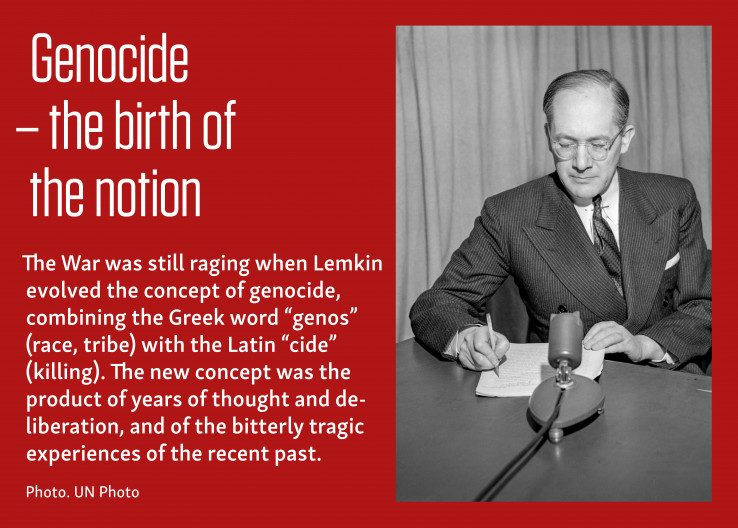

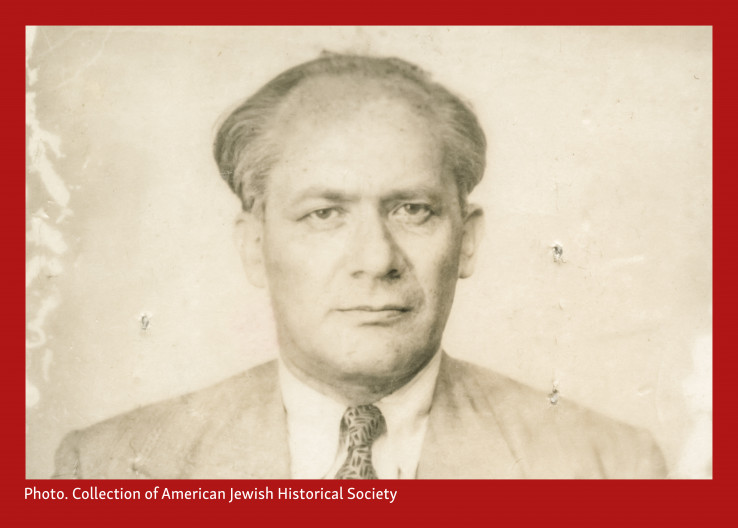

Those present in the conference hall at the Palais de Chaillot passed on their congratulations to Raphael Lemkin – after all, the newly adopted document was commonly referred to as “Lemkin’s convention”. A Polish lawyer of Jewish origin who had lost almost his entire family in the Holocaust, he was the originator of the term genocide, having defined this crime and documented it with examples. Lemkin also prepared the first draft of the Convention and spearheaded a campaign for its adoption. To this day, the document serves as the international community’s principal instrument protecting it from genocide – “the crime of crimes”.

Signing of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, Paris, 11 December 1948.

Chapter 2. Roots

Youth in a shared land

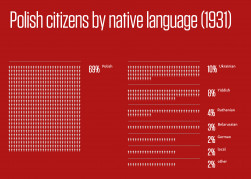

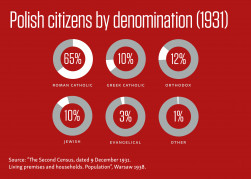

Raphael Lemkin was born on 24 June 1900 in Bezwodna, a village near the town of Wołkowysk, in the Polish lands of the Russian Partition. He spent his childhood on a small farm leased by his parents. After the restitution of independence in 1918, Poland was home to many nations, and the Eastern Borderlands – inhabited by Poles, Ukrainians, Jews, Belarussians and other nationalities – were the most ethnically diverse part of the country.

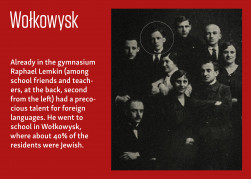

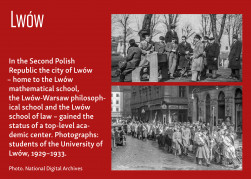

Lemkin graduated from the gymnasium in Wołkowysk and took up law at the Jan Kazimierz University in Lwów – the most important center of jurisprudence and legal thought in the Second Polish Republic. He attended lectures given by eminent Polish lawyers, developing an interest in criminal law, and studied cases of mass killings of national and religious communities.

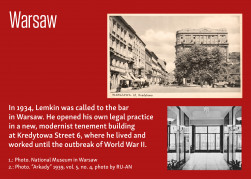

After graduating as a Doctor of Laws, Lemkin began his legal career in Warsaw in 1926, initially working as a public prosecutor and secretary at the Appellate Court in Warsaw. Thereafter he opened a private legal practice. At the same time, he continued his academic career and represented Poland at numerous international legal conferences.

Chapter 3. Inspirations

A crime without a name

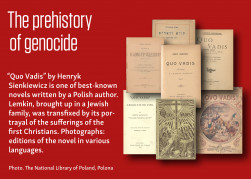

From his early years, Lemkin was deeply moved by the fate of people persecuted on account of their nationality and religion. As a child he read the novel “Quo Vadis” – a famous Polish literary work by Henryk Sienkiewicz – and learnt about the suffering of the Christians in ancient Rome under the rule of emperor Nero.

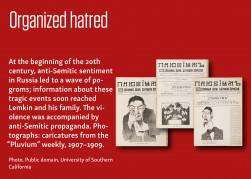

He quickly realized that mass killings were not a thing of the past. In the years 1903-1906, an enormous wave of pogroms of Jews swept through Russia. As a matter of fact, the Tsarist police demanded bribes from Lemkin’s parents, because Jews were not allowed to live outside the Pale of Settlement.

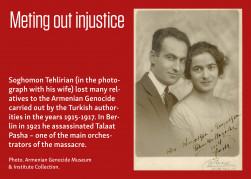

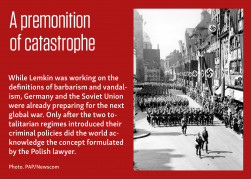

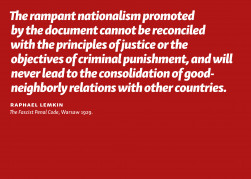

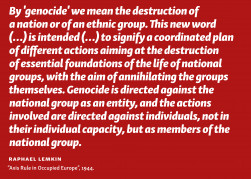

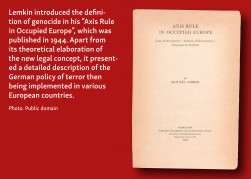

As a young lawyer, Lemkin studied instances of mass crimes perpetrated by state authorities against entire communities. He considered the Armenian Genocide, conducted by Turkey from 1915 to 1917, as a key example of such policy. While studying the criminal law codes of totalitarian states, i.e. Fascist Italy and the communist Soviet Union, Lemkin identified new threats. In preparation for the Conference in Madrid in 1933 he developed definitions of new crimes under international law: “barbarity” and “vandalism”, which later became the foundation of the concept of genocide.

Chapter 4. Experience

Between two totalitarianisms

In 1939, Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union invaded Poland, thus starting the Second World War. The occupied Polish lands soon became the scene of mass crimes. The Germans proceeded to implement their plan of exterminating the Jews and wiping out the Polish intelligentsia, while in 1944 they virtually obliterated Warsaw. Their occupation resulted in the death of between 5,500,000 and 5,700,000 Polish citizens, half of whom perished in the Holocaust.

The Soviets initially focused their apparatus of terror on internal opponents – real and imagined. In the years 1932–1933, they engineered mass hunger engineered in Ukraine, leading to the starvation of some 3,300,000 people. Just before the War, the NKVD murdered some 100,000 Soviet citizens of Polish origin. The invasion of Poland allowed the Soviets to implement their broader strategy of regional domination: thousands of so-called “enemies of the people” were deported deep into the USSR, while in 1940 the NKVD executed more than 20,000 Polish officers in Katyń and other locations.

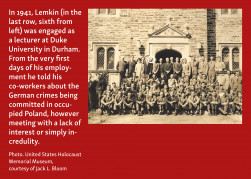

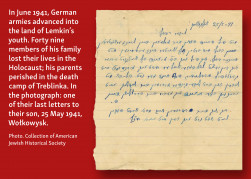

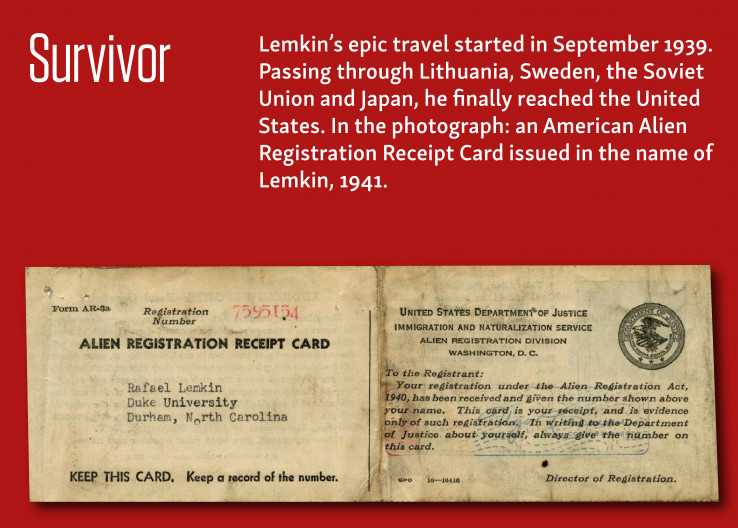

The catastrophe which overtook the Second Polish Republic rapidly evolved into a personal tragedy for Lemkin, who lost nearly his entire family in the Holocaust. He himself escaped to the United States, where he worked on the concept of genocide.

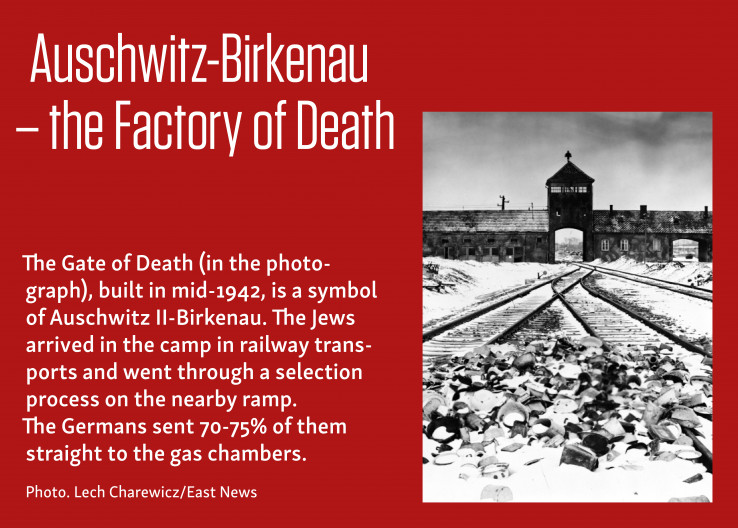

From 1942 on, the Nazi German concentration and extermination camp of Auschwitz-Birkenau functioned as one of the main centers of the Holocaust: within three years, the Germans murdered nearly 1,000,000 Jews there. Immediately upon their arrival at the railway station, the transports underwent a selection. Those unfit for work were sent by the SS men to the “bath”, which was in actual fact a gas chamber. Once the poisonous gas had done its work, the victims’ bodies were burned in the crematoria. Although over the years numerous personal items have been recovered from the site, it is usually impossible to associate them with specific individuals.

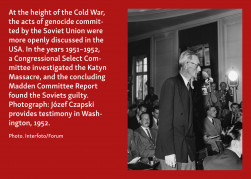

Katyn, a village located near Smolensk, is where the Soviets committed an appalling crime against Polish prisoners of war. On 5 March 1940, the Political Bureau of the All-Russian Communist Party issued an instruction to exterminate more than 25,000 people – “declared and incorrigible enemies of Soviet authority”. In April and May 1940, the NKVD carried out the executions of approximately 22,000 Polish army and police officers, who were at once intellectuals representing a great many professions. The victims were dispatched with a shot to the back of the head, and their bodies were thrown into pits. When the Germans discovered these mass graves in 1943, Soviet propaganda was quick to blame the Nazis for the crime. Such was the official version of events right until the end of Communist Poland in 1989.

The Intelligenzaktion. The testimony of Oskar Stuhr

Oskar Stuhr (1891-1962) – a lawyer and social activist. He was arrested by the Germans in Krakow in November 1939, and subsequently incarcerated for a few months in the prison at Montelupich Street and in Wiślicz. In June 1940, he was deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau in the first transport of Polish prisoners. After the War he testified at the trial of Rudolf Höss, the commandant of Auschwitz-Birkenau.

The Holocaust. The testimony of Henryk Tauber

Henryk Tauber (1917-2000) – a Polish Jew from Chrzanów who worked as a shoemaker. Deported by the Germans to Auschwitz-Birkenau in 1943, he was forced to join Sonderkommando – a work detail operating the gas chambers and crematoria. He participated in the Sonderkommando revolt of October 1944. In January 1945, he escaped during the "death march". After the war he testified at the trial of Rudolf Höss, the former commandant of Auschwitz-Birkenau.

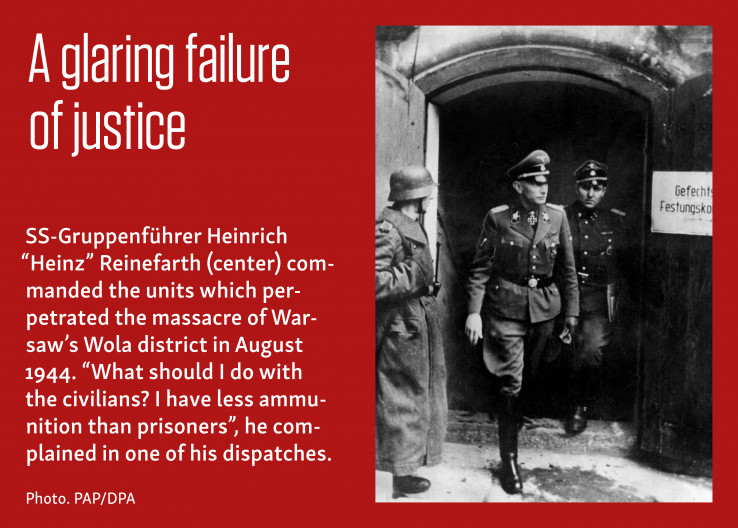

The Wola Massacre. The testimony of Wacława Gałka

Wacława Gałka (born in 1908) – during the Warsaw Uprising she lived with her husband Szczepan, daughter Stanisława, and son Wojciech at Wolska Street 132, near Sowińskiego Park. After the War she testified before the Main Commission for the Investigation of German Crimes in Poland on the subject of the mass executions of civilians in the Wola district of Warsaw.

The Katyn Massacre. The testimony of Stanisław Swianiewicz

Stanisław Swianiewicz (1899-1997) – was a lawyer, economist and Sovietologist. He was captured by the Soviets in September 1939. On 29 April 1940, he was removed from the camp in Kozielsk and taken away in the direction of Smolensk. Luckily withdrawn from a transport of Polish officers selected for execution, he was deported to one of the Gulags. Mr. Swaniewicz was released under the amnesty of 1941, and after the War he went on to lecture in Great Britain, the USA and Canada. He witnessed the initial Soviet preparations for what would evolve into the Katyn Massacre.

Chapter 5. Reckoning

The world after genocide

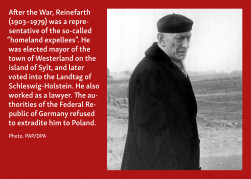

The victory of the Grand Alliance opened up the possibility to carry out a reckoning of German crimes. In the years 1945-1946, Hermann Göring, Alfred Rosenberg and Martin Bormann, among others, were tried before the International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg. 19 of the accused were convicted, 12 of whom were sentenced to death. Further trials were held in the American zone of occupation and in Poland, where Auschwitz-Birkenau commandant Rudolf Höss was tried in 1947. But many German perpetrators escaped punishment.

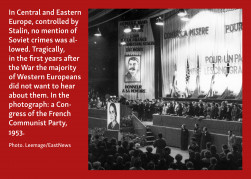

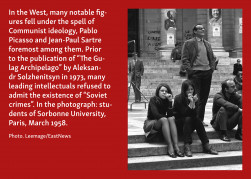

The Soviet Union was amongst the victors of the War, and thus Communist atrocities were not brought to light – not to mention court. Indeed, Soviet prosecutors in Nuremberg even attempted to shift the blame for the Katyn Massacre onto the Germans. For decades, Communist propaganda and the West’s naïve fascination with this ostensibly progressive ideology made it impossible to bring justice to the victims of Soviet totalitarianism.

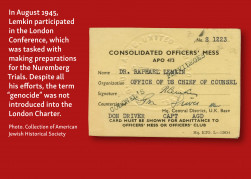

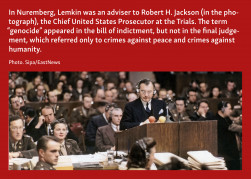

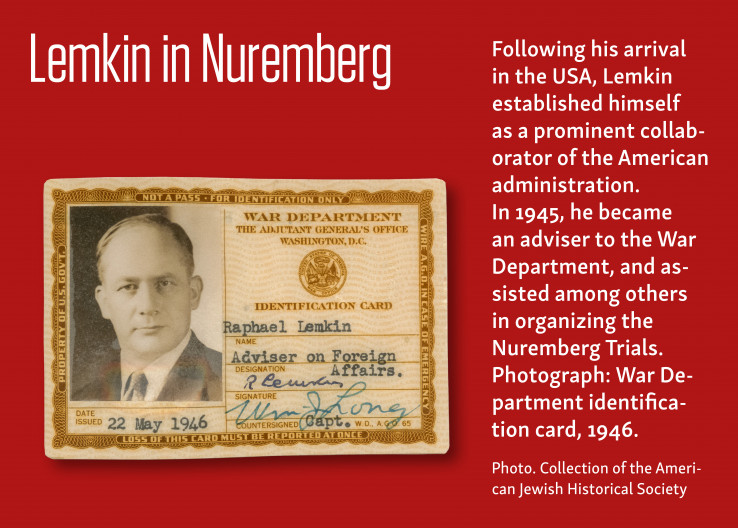

During the Nuremberg Trials, Raphael Lemkin acted as an advisor to the Americans. The term “genocide” did appear in the bill of indictment, but the perpetrators were eventually convicted of other crimes. Lemkin devoted the rest of his life to persuading the world to adopt his concept.

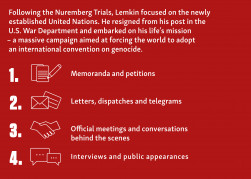

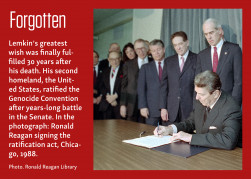

Lemkin spent his final years in seclusion and poverty, being unable to find permanent employment. Nevertheless, he continued to campaign for the ratification of the Genocide Convention by the USA. A few days before his death, he was still working on an autobiography. He died of a heart attack on 28 August 1959.

Chapter 6. Challenges

The legacy of Rafał Lemkin

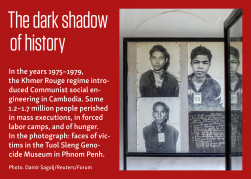

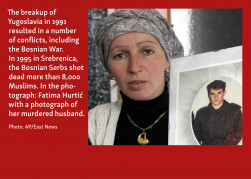

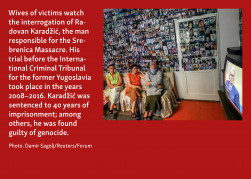

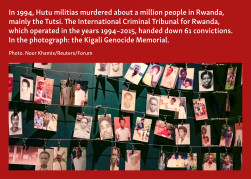

Raphael Lemkin’s work had its roots in the experiences of the Second World War, but it invites universal application, and as such can be used to describe events that unfolded in various parts of the world throughout the 20th century. Even today, the occurrence of mass atrocities endangering the existence of entire national and religious groups testifies to the fact that genocide is an ongoing challenge.

For years, the international community has been building a system for prosecuting and punishing such crimes within the framework of the UNO. Special courts were established to investigate crimes committed in the former Yugoslavia, Rwanda and Cambodia. In 2002, the International Criminal Court began operating as the first permanent international court in history, with competence to deal with the crime of genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, and crimes of aggression.

Raphael Lemkin’s concept revolutionized not only international law: by giving name to the crime of genocide, it helps understand and overcome this extreme experience. After all, the further fate of communities which fell victim to genocide lies first and foremost in their own hands. Will they manage to forge a better future, keeping their tragic experiences in mind and turning them into a source of strength?

"Lemkin. Witness to the Age of Genocide" exhibition

Script and texts:

Bartosz Gralicki

Tomasz Stefanek

Piotr Szlagowski

Graphic design:

Kasper Skirgajłło-Krajewski

Anna Rzeźnik

Beata Dejnarowicz

Translation:

Aleksandra Arumińska

Julia Niedzielko

Maciej Zakrzewski

Digital adaptation:

Anna Miszczyk

Aleksandra Kiereta

Natalia Radulska

Acquisition of materials:

Paulina Wiśniewska

Multimedia:

MOOV

Zobacz także

- Lemkin. Świadek wieku ludobójstwa | wystawa wirtualna

Wystawa wirtualna

Lemkin. Świadek wieku ludobójstwa | wystawa wirtualna

Czy ludobójstwo to domena historii? Co doprowadziło do powstania jednej z najważniejszych odpowiedzi intelektualnych na tragiczne doświadczenie II wojny światowej? Poznaj historię Rafała Lemkina - człowieka, który stworzył pojęcie ludobójstwa!

- Podwójnie Wolne. Prawa polityczne kobiet 1918 | wystawa wirtualna

Wystawa wirtualna

Podwójnie Wolne. Prawa polityczne kobiet 1918 | wystawa wirtualna

Przyznanie kobietom czynnych i biernych praw wyborczych na podstawie dekretu Naczelnika Państwa z 28 listopada 1918 roku stawiało Polskę w szeregu najbardziej demokratycznych i postępowych państw Europy.

- Paszporty życia | portal tematyczny

Wystawa wirtualna

Paszporty życia | portal tematyczny

Zapraszamy do odwiedzenia strony internetowej o działalności grupy polskich dyplomatów, którzy podczas II wojny światowej w szwajcarskim Bernie, we współpracy ze środowiskami żydowskimi ratowali żydów z całej Europy.

- Liberated Twice. The political rights of women 1918 | online exhibition

Wystawa wirtualna

Liberated Twice. The political rights of women 1918 | online exhibition

The Decree issued by the Chief of State on 28 November 1918, which granted women the right to vote and the right to stand for election, placed Poland amongst the most democratic and progressive European states.

- Zawołani po imieniu | wystawa wirtualna

Wystawa wirtualna

Zawołani po imieniu | wystawa wirtualna

Kim są „Zawołani po imieniu”? To Polacy, którzy podczas okupacji niemieckiej zostali zamordowani przez Niemców za pomoc niesioną skazanym na Zagładę Żydom. Losy pomagających przez lata były znane tylko ich najbliższym.