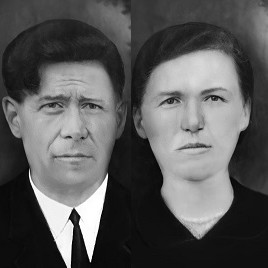

Fedor Bojmistruk (1905-1978) Kateryna Bojmistruk (1909-2000) - Instytut Pileckiego

Fedor Bojmistruk (1905-1978) Kateryna Bojmistruk (1909-2000)

Awarded in 2022.

“I was crying in the barn, next to the corpses of two boys and an elderly man. I was holding a tiny piece of bread in one hand and a handkerchief with two letters in another. The letters were probably my initials.

What were they? I don’t know,” Hanna Muszyd, maiden name Boymistruk, said about the events from many years ago. She did not remember the Volhynia Massacre she had survived at the age of about two. All she knew was what her neighbors had told her.

Her family died on 30 August 1943, when the units of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army murdered some 600 people in the Polish village of Gaj. Two days later, they forced Ukrainian farmers from the nearby village of Kashivka to bury the corpses. In one of the barns, the Ukrainians found a little girl who was walking around the corpses and crying. They decided to take her, despite fearing that the Banderites could burn down and murder their village for rescuing a Polish child. Kateryna and Fedor Boymistruk gave the girl shelter, baptized her in the Orthodox Church and named her Hanna.

The Ukrainian Insurgent Army soon demanded the girl be handed over to them, but Fedor Boymistruk each time refused to give her up: “She is my daughter – you would have to shoot me first.” Following the advance of the front, Fedor was enlisted into the Red Army. Kateryna stayed home with Hanna and on many occasions was forced to hide from Ukrainian nationalists. After Fedor returned from the war, the Boymistruks gave Hanna a loving home and treated her like their own child. “Kids bullied me at school by saying, ‘you are not really your parents’ daughter. You are a Polish foundling.’ I would come home crying, and my mum would hug me and say, ‘do not listen to such nonsense. You are our child and that is all,’” Hanna recalled.

Fedor and Kateryna Boymistruk never told her she was a Polish girl found in the village of Gaj. Hanna learned the truth about her origins as an adult from her adoptive aunt.

Later on, Fedor and Kateryna Boymistruk took her in. There were many children in our household, while they had none of their own. They took her in and raised her like their own daughter. The truth is, they were risking their lives. We all were – if the Banderites found out, they could kill everyone.

See also

- Ilona Andrássy de Csíkszentkirály et Krasznahorka

awarded

Ilona Andrássy de Csíkszentkirály et Krasznahorka

(1917–1990)Following the outbreak of the Second World War, Ilona Andrássy was working together with other aristocrats, established the Hungarian-Polish Refugee Welfare Committee in Budapest.

- Anatolij Giergiel (1904—1981)

awarded

Anatolij Giergiel (1904—1981)

In the summer of 1943 in Volhynia, having learned about a planned attack by Ukrainian nationalists on Poles, Anatolyi Giergiel warned his friend.

- Raymond Voegeli

awarded

Raymond Voegeli

(1894–1980)Helping those in need was the meaning of Father Raymond Voegeli’s life. Before the war, he was a member of the Camillians, whose main mission was ministering to the sick.