Aud Valla - Instytut Pileckiego

Aud Sejlelid, still going by her maiden name at the time, spent her entire life in the small town of Hemnesberget in northern Norway, in a picturesque land of fjords.

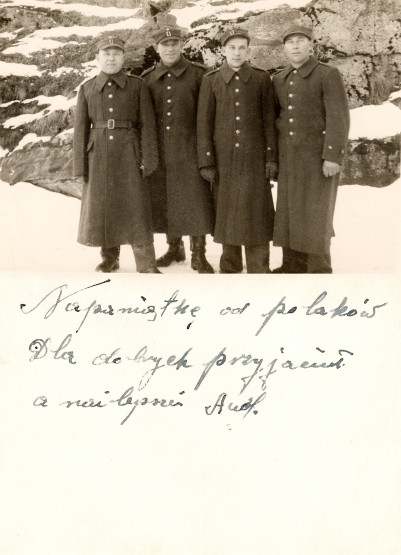

During the war, she first worked in a pharmacy and then was employed as a telephonist at the Norwegian Telephone and Telegraph Company. It was then that she came into contact with Polish prisoners of war, who had been brought to Hemnesberget in the summer of 1942 and imprisoned in a building previously used as a house of prayer. The Germans used the Poles to carry out various kinds of work in the Hemnes municipality. Although the prisoners were constantly guarded, they managed to establish contacts with the local population, which included 20-year-old Aud. She and other girls delivered food and parcels of clothing to the prisoners and wrote letters to them. Aud, however, decided to become even more involved in helping the Poles, which put her at risk of arrest by the Germans – she provided support to the prisoners during their escapes, guiding them across the Norwegian-Swedish border.

On 2 February 1943, Aud helped Jan Szkolny and Alfons Łuczek to freedom, leading them safely to the Swedish border. Later that same month, she helped another Polish prisoner, Jan Mroczek, to escape and accompanied him for much of the way as a guide. When they encountered German guards during their journey, they pretended to be a pair of lovers out for a walk, thus avoiding detection. After the war, Aud married Harald Johan Valla and had one son, Håvard. She held fond memories of the Poles, corresponding with Jan Mroczek and visiting him in Sweden, where he lived with his wife and son. In addition, in the 1980s she became involved in a nationwide collection of aid for Poles organized by the Norwegian Women’s Healthcare Association. The parcels she funded reached families in Szczecin, Gdańsk and Górzno near Piła. Aud Valla passed away on 30 June 2014.

“The second escape I helped with was the last one in February 1943.

I helped Jan Mroczek, a prisoner with whom I corresponded and to whom I sent parcels. […] We agreed that although things were getting stricter in the camp, he would try to get out on certain days. […] The escape went so easily that it really doesn’t bear mentioning. But we narrowly avoided being caught and it all ending in disaster.”

Radio interview with Aud Valla, transcript in the possession of the Pilecki Institute.

See also

- Aleksander Ładoś (1891-1963)

awarded

Aleksander Ładoś (1891-1963)

He was the leader of the group which issued illegal Latin American passports to persecuted Jews. Ładoś gave the group diplomatic protection.

- César de Sousa Mendes do Amaral e Abranches

awarded

César de Sousa Mendes do Amaral e Abranches

(1885–1955)In the 1930s, César de Sousa Mendes was at the height of his diplomatic career. He worked at missions in Africa, Europe, America and Asia. He was Portugal’s Minister of Foreign Affairs for a year.

- Anastasija Koreń (1908–1967) Mykoła Koreń (1905–1944)

awarded

Anastasija Koreń (1908–1967) Mykoła Koreń (1905–1944)

On the evening of 15 July, Mykola’s brother-in-law appeared at the Korens’ doorstep, accompanied by four children of their neighbors, the Adamowiczs: nine-year-old Teresa, five-year-old Janusz, three-year-old Stasia and one-and-a-half-year-old Henio.