Was Stalin a genocidaire? - Instytut Pileckiego

Was Stalin a genocidaire?

An interview with Norman M. Naimark, the author of the "Stalin's Genocide" conducted by Eryk Habowski, an expert in international law at Pilecki Institute.

Eryk Habowski: Genocide is not a phenomenon of the 20th century alone; its history dates back to the ancient times, it has accompanied man from the dawn of time, bearing testimony to the darker side of human nature. The confrontation of the entire states, nations and societies – as well as individuals – with the two worst totalitarianisms of the 20th century was a very singular experience in the history of civilization. Yet while the genocidal character of the German Third Reich raises no doubts, claiming the same about Soviet Russia under Stalin’s rule leads to direct questions: was Stalin a genocidaire?

Norman Naimark: As you are well aware, historians and journalists argue about this very question. I wrote the book, in part, because I kept arguing with my colleagues in the field that it seemed to me that you could call Stalin’s mass killing of the 1930s genocide. Yes, in my view Stalin was a genocidaire. Some genocidal activities of that period spilled over into the wartime period, with his attacks on the Baltic nations, the Poles (at Katyn), and the murderous deportation of the so-called “Punished Peoples,” especially the Chechens and Crimean Tatars.

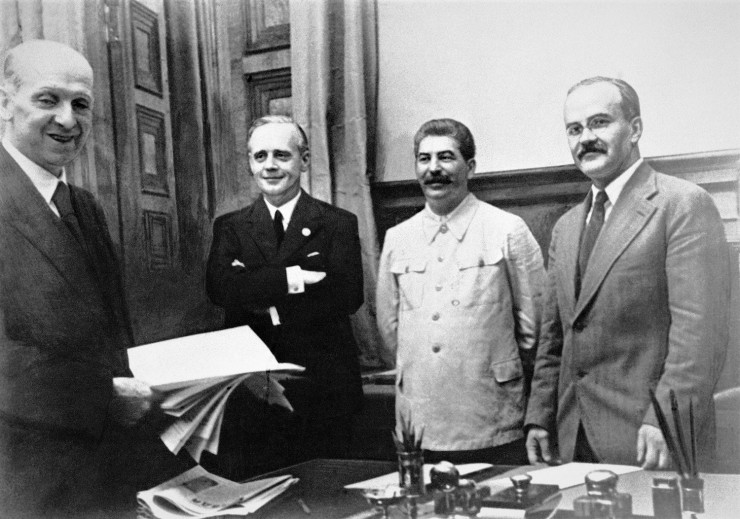

EH: In the article “Genocide Pact”, which is an introduction to the Polish edition of your book, I put forward the thesis about the twin similarity of these two totalitarian regimes, the similarity of genocidal mechanisms and strategy of terror – despite the fact that the political traditions of Germany and Russia have varied over the years. However, disastrous similarities appear in the 1930s, which even lead to criminal cooperation – to the Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact, and – from European and Polish perspective – finally to Soviet occupation of Poland after World War II. Would you agree with this?

NN: Yes, there are many similarities between the Nazi and Soviet regimes. As you know, historians in Germany and the United States, but particularly in the former, have been very reluctant to point out the similarities in the regimes. It’s only been in the past twenty-five years or so that scholars have been willing to explore this question, and then only hesitantly. The two dictators watched one another closely. There are even instances when they praised each other for their "forceful" actions. The cooperation between the regimes in the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact was presaged by a sense of mutual respect. Nevertheless, the pact was primarily about geostrategic questions: for Hitler how to deal with conquering the continent without fighting the British and Soviets at the same time, and for Stalin how to avoid war with Hitler at any cost. Surely the experience of having occupied part of Poland during the 1939–42 period served as a template for Stalin’s later insistence that he would dominate Polish affairs. The borders he achieved in 1939 were certainly the absolute minimum demands he made on his fellow Allies after war broke out with Hitler.

EH: What would you say were the shared characteristics of these two totalitarian regimes? What did these two dictators – Stalin and Hitler – have in common, if we may so assume? Some commentators would like to see them as mad and bloodthirsty tyrants, but it seems that it would be an oversimplification to reduce the question to considerations about the failings of human nature and the matters of psychology, if not psychiatry. After all, their decisions resulted from deliberate and cold-blooded strategies and policies, the operation of state structures and human networks – complex mechanisms of power based on the ideology of a new world whose “system of values” had nothing to do with religion and constituted a systemic denial of values stemming from the two or more thousand years of civilization. What is more, both dictators programmed their states and nations with the use of propaganda tools unavailable before, and introduced change regardless of its cost, including human losses numbering into the millions, the prime example being the German death industry with its system of concentration and death camps and Stalin’s policy that found its fullest expression in the spiraling terror and the Gulag. It was not the states that were the enemy – it was the societies and nations that were murdered, as was duly noticed by Lemkin, among others. What did, then, the Soviet Generalissimus and the Nazi Führer have in common?

NN: I think you are right not to overemphasize the psychology of mass murderers like Hitler and Stalin. But I would not dismiss this aspect of the comparison. It is my view that we would not have had the Holocaust without Hitler and that the kind of genocidal mass killing that went on in the Soviet Union in the 1930s would have been very unlikely without Stalin. Of course, we will never know. But they did share psychological characteristics, including a complete indifference to human suffering; neither had an ounce of empathy for their victims, including those who had been close comrades and friends. Millions could (and did) die – it did not matter to them. (Mao was like that, as well.) Both shared a political philosophy that completely subordinated means to ends. Any means was acceptable as long the ends of the building of their political power and vision of society were advanced. With that said, I think that you are also right that the transformative ideologies of Nazism and Stalinism that imbued both the Third Reich and the Soviet Union played a crucial role in mobilizing and sustaining mass murder. One should also remember that these were police states, where powerful and violent institutions, like the Gestapo and SS, and the OGPU and NKVD, had governmental and social roles that fostered and profited from eliminationist programs.

EH: Your attention is focused on Stalin’s genocidal policy of terror against various nations inhabiting the Soviet territory. What, in your opinion, were the reasons behind such a model of power and the forced introduction of a “Soviet man”? Did they result merely from Stalin’s nature, or maybe the “nature” of the post-revolutionary Soviet state? Or perhaps both?

NN: As usual in history, many factors combine to create a situation where the Soviets became “Nation Killers,” to use the title of one of Robert Conquest’s books. Certainly, we need to begin with Stalin’s policies in the early 1930s to reverse the efforts to encourage national distinctiveness in the 1920s, when it became clear that this would become a brake on the power and influence of the central party and government apparatus in Moscow. Stalin saw himself as an expert on nationalities, and also as someone who understand the power of nationalism. The Soviet Union would remain a federation, according to his developing views, but one deprived of any true political independence on the part of the republics. Stalin could, for example, not destroy all the Ukrainians, but he could break their back as an independent entity, and that’s exactly what he did through the Holodomor (1932–33) and the violent purges against the Ukrainian party, intelligentsia, and clergy in the 1930s. In the case of the Crimean Tatars and Chechens-Ingush during the war, he would try to destroy the nations themselves.

EH: You devote much attention to the Katyn Massacre and the planned murder of the Polish intelligentsia. Stalin never forgot the Soviet defeat in the 1920 Battle of Warsaw – a battle that is rarely remembered but which prevented the mighty Red Army from occupying Poland and the rest of Europe, Berlin and Paris included. Poles managed to block the Soviet advance. In the years 1937–38, Stalin conducted the Polish Operation of the NKVD – based on Order 00485 – which encompassed over 100,000 Poles under Soviet rule; then there was the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. The aim was clear and imperial: to destroy the Polish state and share the spoils with the Third Reich. The spring of 1940 brought immeasurable suffering to tens of thousands of Polish officers and officials who fell into the hands of the Russians. But the key question is, why the Katyn Massacre was a genocide? What in your opinion were Stalin’s motives? And what did the Katyn genocide mean for Poland – for the future of the Polish state?

NN: It is hard conceptually to fit neatly the murder of 22,000 Polish officers and administrators into a “wholistic” attack on the Polish nation, of the sort that Hitler, for example, undertook in the “AB Aktion” and later murderous assaults on Poles. At the same time, the destruction of Poles in the Soviet Union surely influenced Stalin and Beria when they decided to kill the Polish victims of Katyn. It might well be that Stalin felt that the division of Poland with Hitler would be more or less permanent and therefore these “anti-Soviet” Poles within Soviet borders needed to be eliminated like their predecessors in the 1930s. I think you are right about Stalin’s inherent antagonism to the Poles: the Poles would always be enemies, no matter what, and thus needed to be eliminated, if they could not be controlled. In that situation in the spring of 1940, with hundreds of thousands of Polish women and children in distant camps in Central Asia and Siberia, the Katyn events should be looked at as a continuation of the elimination of Poles in the 1930s and thus genocide.

EH: Work on the Convention took quite a long time. At the beginning, the creators (Raphael Lemkin – called the Father of the Convention – and others) wanted the Convention, in reference to the previous Resolution and the drafts, to contain crimes committed for political or social reasons, which ultimately disappeared from the 1948 Convention. Can we put together the thesis here that one of the main reasons was Stalin’s opposition, as he was afraid that most of his own crimes would simply turn out to be genocide?

NN: A new book is soon to be released about the Soviet views of and participation in the Nuremberg Trial by Francine Hirsch that demonstrates the centrality to Stalin and Moscow at Nuremberg of keeping Katyn out of the trial and out of the press. The Soviets were very sensitive about their own history of mass murder and did everything they could to suppress knowledge of it. The Convention was no different. It is also true, as has been demonstrated by a number of scholars, that it was not only the Soviet Union that was deeply interested in keeping social and political crimes out of the convention.

EH: Is the discussion on Stalin’s genocides only a discussion on the history of conflicts in the 20th century or on the history of international law? Or could we say that it is first and foremost a discussion on socio-collective and geo-political mechanisms, relating to the creation of “safety valves” in international relations? Did humanity learn the lesson of the Age of Genocide, as the last century can be referred to? Why can it be significant today for the states that had spent over 50 years in the Soviet sphere of influence?

NN: It is my view that the historical phenomenon of genocide is still with us and will be for a very long time. The importance of the convention and the jurisprudential literature developed after it, primarily in the trials of Bosnian and Rwandan genocidaires, can be seen in the development of the International Criminal Court and its ongoing activities in connection with Sudan and Syria. These lessons are important for everyone: American citizens who have had the good fortune of living for more than two centuries under the rule of law, as well as Polish citizens, who were forced to endure almost a half century of Soviet domination and communist rule. The study of genocide tells us that no societies are exempted from its terrible potential.

See also

- Competition for the position of Adjunct in the Humanities, Department for the study of Nazism and German occupation during the Second World War

News

Competition for the position of Adjunct in the Humanities, Department for the study of Nazism and German occupation during the Second World War

We invite you to participate in the competition for the position of Adjunct in the Humanities, Department for the study of Nazism and German occupation during the Second World War.

- PORTRAITS | Adam Bałdych Quintet

News

PORTRAITS | Adam Bałdych Quintet

“Portraits” is a moving story told through sound, in which jazz meets history and individual fates intertwine with the collective experience.

- Competition for the position of Adjunct in the Humanities

News

Competition for the position of Adjunct in the Humanities

Competition for the position of Adjunct in the Humanities, Department for the study of Nazism and German occupation during the Second World War at the Witold Pilecki Institute of Solidarity and Valor.

- Merry Christmas!

News

Merry Christmas!

On the occasion of Christmas, we wish you all the best and every success in 2026.

- The Lemkin Laboratory – the Pilecki Institute and the Mieroszewski Centre sign cooperation agreement

News

The Lemkin Laboratory – the Pilecki Institute and the Mieroszewski Centre sign cooperation agreement

- 2025 | Michał Bilewicz, „Traumaland. Polacy w cieniu przeszłości"

News

2025 | Michał Bilewicz, „Traumaland. Polacy w cieniu przeszłości"

Michał Bilewicz’s “Traumaland. Polacy w cieniu przeszłości” (Wydawnictwo MANDO/Wydawnictwo WAM) won the Witold Pilecki International Book Award in the “academic history book” category.

- 2025 | Emil Marat „Bratny. Hamlet rozstrzelany"

News

2025 | Emil Marat „Bratny. Hamlet rozstrzelany"

The book “Bratny. Hamlet rozstrzelany” (Wydawnictwo Czarne) won the Witold Pilecki International Book Award in the “historical reportage” category.

- Maksym Eristavi, Russian Colonialism 101. How to Occupy a Neighbor and Get Away with It. An Illustrated Guide

News

Maksym Eristavi, Russian Colonialism 101. How to Occupy a Neighbor and Get Away with It. An Illustrated Guide

Maksym Eristavi’s “Russian Colonialism 101. How to Occupy a Neighbor and Get Away with It. An Illustrated Guide” (IST Publishing) won the the Witold Pilecki International Book Award in the “special prize” category.

- The Witold Pilecki International Book Award: Bilewicz, Marat and Eristavi winners of the Institute’s 5th competition for best history book

News

The Witold Pilecki International Book Award: Bilewicz, Marat and Eristavi winners of the Institute’s 5th competition for best history book

The Witold Pilecki International Book Awards were presented during a ceremony on Thursday 11 December, in the auditorium of the Pilecki Institute.

- Conference summary “Die Haltung der deutschen Minderheiten im besetzten Europa (1939–1945). Forschungsmethoden, soziale Kontexte und Nachkriegsfolgen”

News

Conference summary “Die Haltung der deutschen Minderheiten im besetzten Europa (1939–1945). Forschungsmethoden, soziale Kontexte und Nachkriegsfolgen”

On 20–21 November 2025, an international academic conference was held in Berlin and addressed issues of the attitudes of the German population during the occupation and their postwar fate.

- Results of the Competition for the position of Manager of the Extraneous Branch of the Witold Pilecki Institute of Solidarity and Valor in Berlin

News

Results of the Competition for the position of Manager of the Extraneous Branch of the Witold Pilecki Institute of Solidarity and Valor in Berlin

Warsaw, 20 November 2025 | Announcement of the results of the Competition for the position of Manager of the Extraneous Branch of the Witold Pilecki Institute of Solidarity and Valor in Berlin.

- Nominations for the Witold Pilecki International Book Award 2025 (fifth edition)

News

Nominations for the Witold Pilecki International Book Award 2025 (fifth edition)

We know the authors nominated for the fifth edition of the Witold Pilecki International Book Award! Out of 60 submissions, the Awards Committee has selected 12 publications to compete in three categories.