The commemoration of Aniela Nizioł who was murdered for helping Jews during the German occupation | CALLED BY NAME - Instytut Pileckiego

The commemoration of Aniela Nizioł who was murdered for helping Jews during the German occupation | CALLED BY NAME

On 3 December 2023 in Łańcut, as part of the “Called by Name” program, the Pilecki Institute commemorated Aniela Nizioł who was murdered for aiding Jews during the German occupation. This was our 35th event commemorating the victims – Jews designated for annihilation and those who lost their lives because they attempted to help them.

In a letter to the participants of the event, Speaker of the Sejm Szymon Hołownia highlighted that Aniela Nizioł was a hero who sacrificed her life for others.

The Speaker highlighted that lending aid to the persecuted in occupied Poland was punishable by death. “This heroic protest against the blatant disregard for freedom and human dignity is now an important point of reference to us. It is our duty to remember Aniela Nizioł and other heroes who attempted to help Jews,” wrote Hołownia.

He stressed that the commemorative plaque unveiled during the ceremony should be a symbol of truth about our wartime past. “At the same time, it should also symbolize the victory of solidarity over hatred and of good over evil,” he added.

The Director of the Pilecki Institute, Prof. Magdalena Gawin, noted in her speech that the scope of the “Called by Name” program has reached nearly the entire country.

“I would like to stress one thing – these commemorative events are not sad. They are joyous. All of the commemorated victims such as Aniela Nizioł died in humiliation, but we have gathered here today to call them by name and restore their memory among the local communities. What can be more joyous than that? We remember them today and we always will,” added Prof. Gawin.

According to the Director of the Pilecki Institute, we must cultivate and preserve our memory, as it can serve as a “powerful tool for attack and defense.”

During the ceremony, a relative of Aniela Nizioł, Elżbieta Gwizdak, delivered a speech in which she thanked the event organizers for commemorating her loved one.

“Aniela was my father’s aunt. She took him and his sister Eleonora in when they were very little, and raised them after their mum died. They all lived in Łańcut. My sister, my two brothers and I are Aniela Nizioł’s closest living relatives,” she said.

Gwizdak added that the commemoration was a tribute to everyone who helped others during the occupation.

“I hope their actions will inspire the future generations to choose the path of kindness, justice and remembrance,” she said.

The story of the Nizioł and Wolkenfeld families

On 9 September 1939, German units entered Łańcut. After the General Government was established, the town became part of the Jarosław district. The policy of terror introduced by the Germans was enforced by the police and the military. Starting in late October 1939, opposing the German authorities or German nationals was punishable by death, as was engaging in acts of resistance against the occupation authorities. The Germans introduced numerous policies and carried out operations with the intention to persecute the citizens of occupied Poland. In the autumn of 1939, among the victims of this persecution was the local intelligentsia in Łańcut. The arrestees were detained for two weeks at the Rzeszów castle as a warning to the locals that was meant to discourage them from engaging in any form of resistance on the National Independence Day (11 November). The Łańcut Jews, who constituted about one third of the town’s population numbering 7,500 inhabitants in the 1930s, were subjected to particularly severe repression. As a result of the Germans’ actions, dozens of the local Jews were humiliated, beaten and robbed, while hundreds were exiled to the Soviet-occupied territories across the San River and replaced by the Jews deported from the territories incorporated into the Third Reich. This was the beginning of the suffering inflicted on the Jewish community, which inhabited the town since the 16th century.

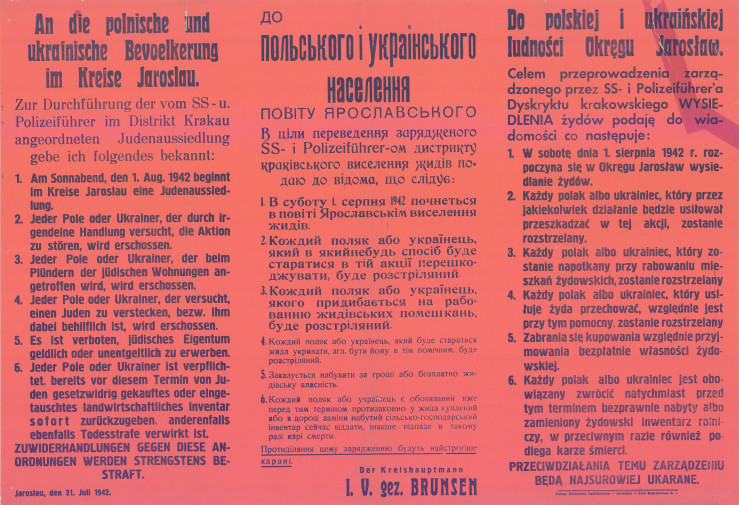

Photograph: On 31 July 1942, the occupation starost of the Jarosław district issued an order to “deport Jews.” The document included a reminder that Poles and Ukrainians would receive the death penalty for helping Jews. The Museum of Jarosław – the Orsetti Tenement Building.

While the Germans did not set up closed ghettos in the Jarosław district, they forbade Jews from leaving their town or village of residence until the end of 1941. In the last days of July 1942, the occupation authorities announced that deportations of Jews inhabiting the district would commence on 1 August 1942. Two days later, on 3 August, the Germans began transporting the Jewish inhabitants of the town and its vicinity to the transit camp in Pełkinie. From there, the Jews were to be sent to the extermination camp in Bełżec. All attempts to help the deportees – even by purchasing some of their items – were forbidden under pain of death.

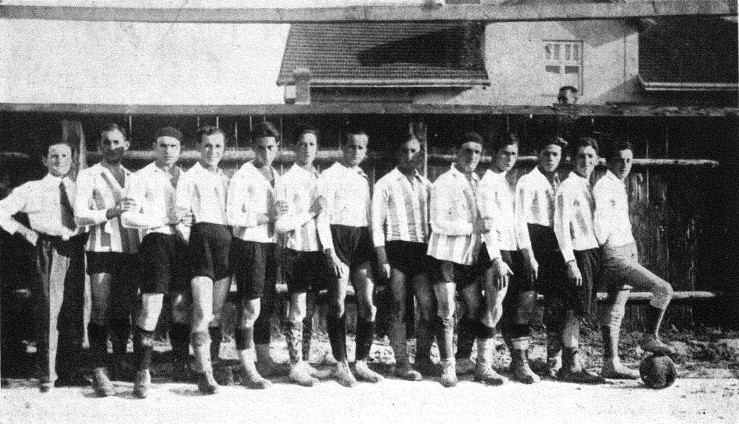

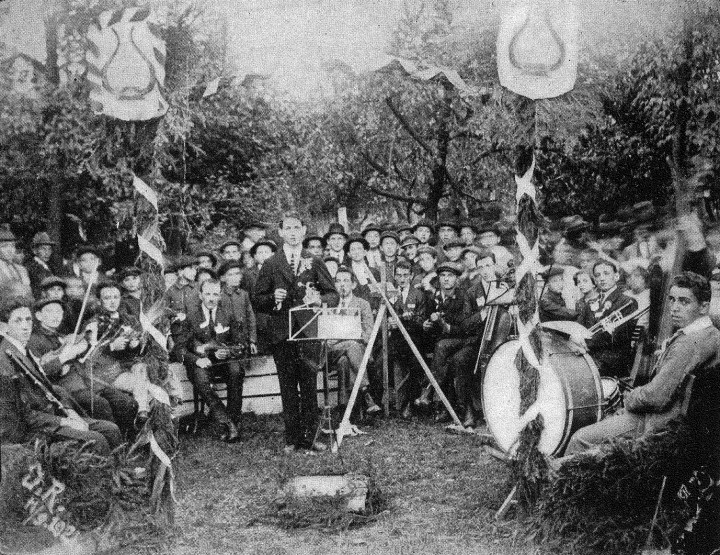

In order to survive, many Jews went into hiding. Among them were members of one of the oldest and most famous families in Łańcut – the Wolkenfelds, who ran a restaurant in Łańcut, managed the Merchant-Agricultural Bank, and had a mill in the neighboring village of Albigowa, previously owned by the Potocki family. In the late 1930s, the owner was Kalman (Kellman) Wolkenfeld (born 1906), known among the locals for playing in the football section of the Jewish “Trumpeldor” Sports Club and in the “Hazamir” orchestra.

Photograph: The football team of the “Trumpeldor” Sports Club in Łańcut, among the athletes is Kalman Wolkenfeld (fifth from the right). This Zionist club was comprised of the youths from wealthy households. “Lancut: hayeha ve-hurbana shel kehila yehudit” [Lańcut: The Life and Destruction of a Jewish Community], eds. Michael Waltzer and Nathan Kudish, Tel Aviv 1963

Around 10 August 1942, Kalman Wolkenfeld, with his wife Lieba Sara (née Feingold, born 1912 in Kańczuga) and son Chaim (born 1937) found refuge at the Nizioł family’s large house on Kraszewskiego Street (at the time: Przecznica) in Łańcut. They were brought to that location by a member of the Union for Armed Struggle – Home Army, a blue policeman named Antoni Głowniak.

The residents of the house were Aniela Nizioł (born 1889, most likely in Huta Laura near Siemianowice Śląskie) and her husband Michał Nizioł (born 1890 in Wola Rafałowska). Michał had a tailoring workshop specializing in women’s clothing. Before the war, the couple raised the two children of Aniela’s brother, after their mother had died. Both Gerard (born 1911) and Eleonora (born 1918) were living elsewhere with their spouses during the occupation.

Photograph: The Nizioł family in the yard at 38 Kraszewskiego Street in Łańcut ca. 1932. Standing from the left: Michał Nizioł (1890–1966), his sister – most likely Julia, Eleonora Kubińska (1918–1998) and her brother Gerard (1911–1987). Sitting from the left: Aniela Nizioł (1889–1942), NN (most likely Bronisława, the stepmother of the Nizioł siblings), NN (most likely Józefa Sołkiewicz, Michał’s sister). Collection of Elżbieta Gwizdak.

The Wolkenfelds stayed in the attic and the cellar of the house for several days. According to one account, one day a random woman from the neighboring village entered the Niziołs’ yard to sell eggs. She allegedly saw Lieba Sara and told a German informer named Kraus about the Jews staying at the house on Kraszewskiego Street. The Jews who were hiding at Michał Nizioł’s house were denounced to the German gendarmerie by Feliks Kraus, a Volksdeutscher known around Łańcut, who told me this himself[1] – from the account given years later by Franciszek T.

The Nizioł family’s neighbor, Roman Kwolek, reported on what happened next: I saw two German gendarmes wearing green uniforms […]. I recognized that one of them was Kokot and the other was, I think, Dziewulski […]. I saw that Kokot’s sleeves were rolled up and he was holding a small, curved Jewish walking stick. They both entered the house of witness Michał Nizioł. […] Having reached Kraszewskiego Street, I turned left […], I looked behind me to see where the gendarmes would go. On my way […] I ran into Michał Nizioł, who was walking towards Kraszewskiego Street […] and I said to him: “dear neighbor, the gendarmerie is at your house”[2].

Having received this warning, Michał Nizioł did not return home – he hid nearby and went back to the house only after making sure that the gendarmes had gone. Years later he talked about what he had learned at that time: my wife Aniela Nizioł, who has since passed away, informed me that the German gendarmes had arrived at the house. Among them was Józef Kokot and the German informer and Volksdeutscher Feliks Krauze. The woman and her son who had been hiding at my house were marched outside into the garden and shot there by Józef Kokot, […] while the Jewish man by the name of Wolkenfeld attempted to flee near the neighbor’s house, where Feliks Krause caught up to him and led him to Józef Kokot, who then shot him[3].

A cart driver for the magistrate was summoned to transport the bodies of the Wolkenfelds. Kalman, Lieba Sara and Chaim were most likely buried at the new Jewish cemetery. Aniela advised Michał to leave the town, fearing that he could be in danger as the owner of the house which served as the hideout for Jews. Nizioł left for Radom on the same day. As for herself, Aniela did not believe she would be in danger. As a Silesia-born woman, she spoke to the gendarmes in German – the language she had known since she was little. She was also acquainted with the gendarmerie’s associate Feliks Kraus, whom her husband had known since childhood. At first, the actions of the Germans seemed to support her belief. During that tragic month of August 1942, similar incidents happened at other locations – the Germans killed the Jews who had gone into hiding, but no Christians in the neighborhood had been persecuted for helping them. Aniela also was not beaten or arrested. But her situation was different, as in most cases Jews were hiding in their own houses and gardens, without any involvement of Poles.

Aniela’s husband described the course of events in his testimony: Several days later, my wife’s friend, Helena Mazanek, residing in Łańcut, arrived in Radom and informed me that my wife had been shot following a death sentence she received at the Gestapo Headquarters in Jarosław[4].

According to Michał’s testimony, several days after murdering the Wolkenfelds, the German gendarmes sent a messenger to his wife in order to summon her to the station. She ignored the summons, so on the following day, 23 August, she was arrested by the gendarmerie and taken to the station. On that day, the Germans were preparing to execute a large group of Jews who had been captured in a hideout by the market square after they were uncovered most likely by Feliks Kraus. Aniela was interrogated and, perhaps due to an oversight – sent to the court building without a German escort.

In 1958, Franciszek T. testified as follows: I learned from the prison warden Stanisław Guźlak that Aniela Nizioł didn’t want to escape, even though her life was in danger. Apparently she was given a chance to flee – she was released home and later went back to the court. Guźlak told her she would be executed that day. Guźlak added that if I came over in the evening I would be able to watch the execution. He also told me to tell her to go home if I ran into her. Indeed, I went to the tax office that evening and when I entered the corridor in the courthouse, I saw Mrs. Nizioł sitting on a bench. I told her not to wait there and to go home, […] I think I even told her to go to my house. She said that she wasn’t going anywhere and that she wasn’t afraid, because she was innocent […]. I went to my office and left the door slightly open […] to find out what would happen to Mrs. Nizioł. At one point I heard a conversation between her and Kokot. It sounded like Kokot wanted to take her to the court yard and she wanted to walk outside into the street. Then I heard them walk towards the court yard, so I went up to the window and saw Mrs. Nizioł walking first […], while Josef Kokot was walking behind her, some one meter away. At some point Mrs. Nizioł turned back and said to him: “are you going to shoot me?” That’s when […] Kokot shot her in the face with his pistol, killing her on the spot. Kokot walked away. Mrs. Nizioł’s body fell to the ground and was left there until the next morning[5].

On the following day, 24 August 1942, Aniela Nizioł was buried at the cemetery in Łańcut.

Volksdeutscher Feliks Kraus was executed by the Polish underground resistance in July 1944.

Michał Nizioł returned home only after the German occupation came to an end. In 1947 he gave a testimony concerning the death of his wife and the activities of German gendarmes in Łańcut. In 1958, he appeared before the judge as a witness at the beginning of the trial of his wife’s murderer, a German gendarme by the name Józef Kokot, who was accused of committing many murders in and near the town of Łańcut. He was involved in the murder of the Ulma family who had been hiding the Jewish Goldman family. During the trial, Kokot denied having murdered Aniela Nizioł. Despite the testimonies of eyewitnesses, he maintained that he was not involved in her death or the deaths of the Wolkenfelds. He was eventually sentenced to death, but the sentence was then changed to imprisonment. He died in prison in 1980.

Photograph: Józef Kokot (standing, first from the left, marked with the symbol “X”). On 23 August 1942 he murdered Aniela Nizioł, and several days earlier he had killed the Wolkenfeld family with another gendarme (most likely Michał Dziewulski). During the trial in 1958, he received 48 murder charges as perpetrator or accomplice. As a result of his actions, about 150 people were killed. State Archive in Rzeszów, fonds 406 Zbiór fotograficzny [Photographic collection], file no. 1962.

In 2016, Yad Vashem – the Israeli Holocaust Martyrs’ and Heroes’ Remembrance Authority – awarded Aniela Nizioł the title of Righteous Among the Nations for helping the Wolkenfeld family.

More about the “Called by Name” program

(PAP)

[1] Protokół przesłuchania świadka Franciszka T. z 9 lutego 1957 r. [Witness interview report of Franciszek T. from 9 February 1957], AIPN Rz 107/1608, vol. 1, p. 89

[2] Protokół rozprawy głównej, zeznania świadka Franciszka Kwolka z 23 lipca 1958 r. [Minutes of the main court session, testimony of witness Franciszek Kwolek from 23 July 1958], AIPN Rz 107/1608, vol. 4, p. 56

[3] Protokół przesłuchania świadka Michała Nizioła z 31 stycznia 1958 r. [Witness interview report of Michał Nizioł from 31 January 1958], AIPN Rz 107/1608, vol. 1, p. 207

[4] Protokół przesłuchania świadka Michała Nizioła z 31 stycznia 1958 r. [Witness interview report of Michał Nizioł from 31 January 1958], AIPN Rz 107/1608, vol. 1, p. 208

[5] Protokół przesłuchania świadka Franciszka T. z 10 maja 1958 r. [Witness interview report of Franciszek T. from 10 May 1958], AIPN Rz 107/1608, vol. 2, p. 173