Ferdinánd Leó Miklósi - Instytut Pileckiego

As a 21-year-old in 1910, he was a member of the Hungarian delegation that participated in the unveiling of the Grunwald Monument in Kraków.

This event, which brought together some 150,000 Poles – at the time deprived of their own homeland – had a strong impact on Ferdinánd’s entire life. It was then that he became an ardent popularizer of Polish affairs in Hungary. During the First World War, he chaired the Union of Hungarian Legionnaires, which brought together Hungarian citizens fighting in the Polish Legions. Not only did he recruit soldiers, but also for a time actively participated in the armed struggle. Furthermore, he intervened with Hungarian authorities on the issue of supplying Poles with weapons and ammunition. In the inter-war period, he played an important role in developing Hungarian-Polish commercial and cultural contacts. In 1930, he became head of the Union of Polish Legionnaires in Budapest, renamed the Association of Hungarians Legionnaires in January 1939. Miklósi initiated and co-financed the erection of a number of memorials related to Polish history, including a monument to Józef Bem in Budapest.

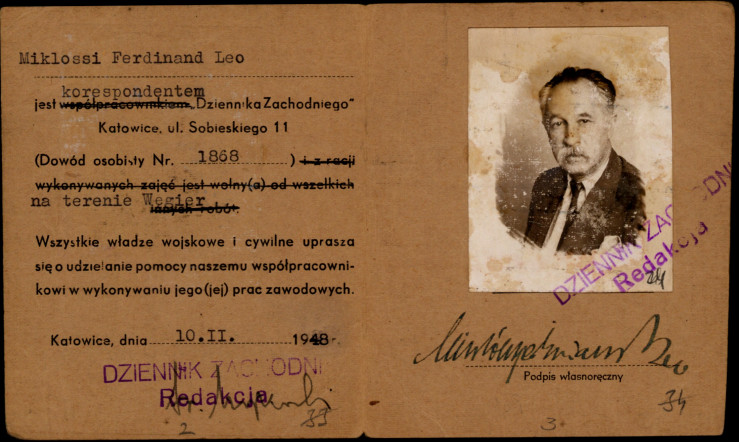

During the Second World War, he was a trusted associate of József Antall, a great friend of the Polish people. Already in early September 1939, he went to the Hungarian-Polish border to help in the admittance of refugees. He organized lodging and food. Acting under various pretexts, Ferdinánd visited refugee camps, where he handed over clothing, documents and secret instructions. He secretly supported the evacuation of interned soldiers to France, while his apartment in Budapest served as a hideout for Polish liaison officers. He reported on the situation of refugees in articles published in the foreign press, and also edited a newspaper, the “Węgierski Kurier Polski”. In May 1944, he was arrested by the Gestapo on charges of illegally helping Poles and sentenced to death. He was spared, however, thanks to the intervention of the Hungarian government. After the war, he worked for a time as the Hungarian correspondent of the Katowice-based “Dziennik Zachodni”. But he was persecuted by the Hungarian Communists, and in 1951 he and his family were evicted from their apartment. He died in poverty on 4 August 1968 in Budapest.

My contacts with Miklósi were not limited to receiving important information and writing articles for him. In fact, I turned to him in all instances when I had any difficulties in taking care of affairs at the [Polish] Institute in Budapest. Feri always found a way out.

A recollection by Zdzisław Antoniewicz, Deputy Director of the Polish Institute in Budapest during the Second World War: Z. Antoniewicz, Rozbitkowie na Węgrzech. Wspomnienia z lat 1939–1946, Warszawa 1987, p. 115.

See also

- Žofia Lachová (1907–1979)

awarded

Žofia Lachová (1907–1979)

The courage and selflessness of Žofia and Jozef Lach helped save many Poles and ensured that the transit route to Poland was in use until almost the end of the war.

- Aristides de Sousa Mendes do Amaral e Abranches

awarded

Aristides de Sousa Mendes do Amaral e Abranches

(1885–1954)In the first months of the Second World War, Bordeaux in southern France seemed like a safe place – deep behind the front, far from the border of the Third Reich.

- Elna Gistedt-Kiltynowicz

awarded

Elna Gistedt-Kiltynowicz

(1895–1982)Warsaw audiences adored her. For Elna Gistedt from Sweden, Poland became a second home when she married industrialist Witold Kiltynowicz in 1922.