The commemoration of Mieczysław Żemojtel and Anna Kowalska | CALLED BY NAME - Instytut Pileckiego

The commemoration of Mieczysław Żemojtel and Anna Kowalska | CALLED BY NAME

On 21 June 2023 in Somianka (Mazovia), a commemorative plaque was unveiled to honor Mieczysław Żemojtel, who was murdered by the Germans for helping Jews during the German occupation, and Anna Kowalska, whom he was helping. It was the 32nd commemoration organized as part of the “Called by Name” program.

The ceremony began at 11 a.m. with a mass at the Church of St. Stanislaus, Bishop and Martyr in Somianka. After the service, the plaque was unveiled at the premises of the Local Social Welfare Center in Somianka.

“We have gathered here today to ‘call by name’ Mieczysław Żemojtel and Anna Kowalska. When the Germans were committing this crime, they hoped that we wouldn’t remember; that no one would recall the victims’ names, that no one would ever light a candle or erect a stone. But today we defy their wishes, as this is the cornerstone of the program – to remember. We are here to restore memory and to gather the local community around this exceptional example of heroism, bravery and humanity. We will always remember,”

said Prof. Magdalena Gawin, Director of the Pilecki Institute, during the unveiling of the plaque.

The event was attended by Sylwester Dąbrowski, Vice-Voivod of the Mazowieckie Voivodeship; MP Anna Siarkowska; Prof. Magdalena Gawin; Andrzej Żołyński, Head of the Somianka Commune; Artur Hofman, President of the Social and Cultural Association of Jews in Poland; Mirosława Korycka, granddaughter of Mieczysław Żemojtel; Joanna Bara; and the residents of Somianka.

“As long as a human is a human, they will make the right choices. Even at the most difficult times. And then they know how to behave decently. If they cannot help – they don’t help, but at the same time they don’t denounce. We should remember about this when we, the Polish society, are being told that we were perhaps too passive. No: even if someone was passive, it meant that they had a family, that they were afraid, as they had a right to be. As for those who behaved so heroically – their hearts beat to a different rhythm – they were of the kind between humans and angels,” said Artur Hofman, President of the Social and Cultural Association of Jews in Poland.

The story of Mieczysław Żemojtel and the Kowalski siblings

After the defeat in the defensive war of 1939, the majority of Polish lands were placed under German occupation. The village of Somianka found itself in the Ostrów county (Kreis Ostrow) in the Warsaw District of the General Government. Following the policy of economic exploitation of the occupied territories, the Germans took over administration of the huge estate of Władysław Müller. The owner had to move to the steward’s house, while his manor was to serve the purposes of the German administration of the Somianka estate. A German, Karol Rubach, was appointed a new administrator. He was to be assisted in his work by the Polish steward, Mieczysław Żemojtel.

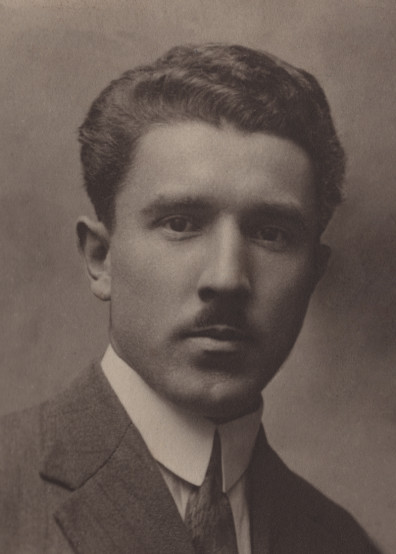

Mieczysław Żemojtel was born in 1898 in the Wilno region. He supported the Second Polish Republic at the time when its borders were being forged, for which in 1933 President Igancy Mościcki decorated him with the Medal of Independence. At the beginning of the 1920s, Żemojtel moved to Warsaw, started a family and worked as a clerk at the Postal Savings Bank. According to family story, at the beginning of the occupation he helped a befriended Jewish family carry out financial operations that were forbidden by the Germans. For this he was allegedly dismissed from his post, and thus he had to leave his wife and two children in the capital city and accept the job in nearby Somianka.

In the autumn of 1940, the Germans established a ghetto in the capital – approx. 450,000 Jews from Warsaw and the vicinity were crowded into a small area. Prevalent hunger and disease prompted many people to attempt escape from the ghetto. Perhaps such fugitives were the two young Jews remembered as siblings: Anna (Hania) and Marian (Moniek) Kowalski. They came to Somianka probably in the spring of 1941. According to the witnesses, Anna was about 18–20 years old at the time, and Marian was a few years younger. Żemojtel gave them employment, thus allowing them to stay legally at the estate. Many employees knew that Anna and Marian were Jews. Both of them worked at the manor and lived either in the attic or in the basement.

The testimony of Marianna Stępkowska:

Sometime in the summer of 1941, a young Jewish woman, about 18 years old, came to the estate with her brother, who was about two years younger. She would clean the yard and sweep corridors, for which the siblings received food. Maria Krawczyk and I gave her clothes and often food. I don’t know her name. She said her name was Anna Nizińska, but others said her name was Kowalska. I called her by her name – Andzia. We called her brother Marian.

When news of various extermination operations aimed against the Jews started reaching Somianka, Anna and Marian went into hiding.

Since October 1941, helping Jews was punished by death in the General Government. Despite the threat, however, Żemojtel continued to help the siblings. He was assisted in this by other people employed at the manor: two young women, Marianna Krawczyk and Marianna Stępkowska, as well as the housekeeper, Maria Kroczewska. They provided the hiding siblings with food and clothing.

In the last days of October 1942, several gendarmes from the station in Wyszków arrived at the manor in Somianka. They knew about the Jews, because someone had probably denounced them. The Germans searched the building and found Anna; Marian managed to escape. They tortured the girl to make her name those who provided her with help. Despite their cruelty, the victim remained tight-lipped and didn’t betray anybody. The gendarmes realized that they wouldn’t learn anything from Anna, and then they decided to kill her. A twenty-something gendarme Henrich Sichau, a man notorious for his brutality, and his colleague led Anna out by a side exit. She was shot a few meters away from the manor.

The testimony of Władysław Staniszewski:

When I went out, I saw a German gendarme standing on the stairs by the entrance to the manor; another gendarme was leading the Jewish girl Ania down the path leading into the park. When she was a few steps ahead of him, he pulled out his gun and shot at the back of her head; the girl then fell to the ground.

The testimony of Marianna Krawczyk:

[…] I went to the manor. As we were passing by the well, I noticed the Jewish girl laying face down close to the side entrance to the manor. I didn’t know that the gendarmes were nearby, so I approached her and called her by her name. Then the gendarme, Heniek, hit me with his rubber baton and chased me away from the corpse.

Anna’s steadfast attitude during the interrogation meant that the Germans had no grounds to carry out an immediate execution of her Polish helpers. They thus ordered Żemojtel to gather all people working in the building, assuming that they must have known about the hiding Jews. Mieczysław brought Marianna Krawczyk and Marianna Stępkowska, warning them that Anna hadn’t betrayed them despite torture. After another interrogation of the entire group, the gendarmes left Somianka, having arrested Rubach and Żemojtel. The German administrator was soon released, while Żemojtel was kept in custody in Wyszków. On or around 10 November 1942, the three women who were helping the Jewish siblings were also arrested, but thanks to Anna Kowalska’s steadfast attitude the Germans had no proof of their assistance, which probably saved their lives.

The four arrestees were transported to Ostrów Mazowiecka, and from there to Pawiak prison in Warsaw. Next they were deported to the Majdanek concentration camp (KL Lublin). Żemojtel arrived there on 13 March 1943. He survived only a few days – he perished at the camp on 19 March. Two months later, his family learned about his fate. The women were released from the camp towards the end of May 1943. They survived the war.

The body of Anna Kowalska (according to one account) was buried near the execution site. In 1958, her remains were exhumed and moved to the Warsaw Insurgents Cemetery. Marian Kowalski managed to avoid arrest. His fate remains unknown.

The stories of those “Called by Name” are always extraordinary, and such is the story from Somianka: Mieczysław Żemojtel, a recipient of the Medal of Independence, the father of the family, who provided Jewish siblings with shelter at the manor; members of his family – the son who died as a Home Army soldier, the daughter who participated in clandestine teaching. A young Jewish girl, known as Anna Kowalska, whose steadfast attitude during brutal ‘interrogation’ by German gendarmes saved the lives of three women employed at the estate who took part in helping the siblings; two of these women were roughly the same age as Anna, says Kamila Sachnowska, head of the “Called by Name” Department.

In 1944, Karol Rubach was accessory to the murder of Władysław Müller, the rightful owner of Somianka. He himself died during the Warsaw Uprising.

Heinrich Sichau, the gendarme who was responsible for the murder of Anna Kowalska and other people in the Wyszków area, was brought before a German court in the 1970s. In 1979, the proceedings were discontinued due to his ill health. Sichau died in 2003 at the age of 85.

The proceedings […] of the Prosecutor’s Office in Düsseldorf against the suspect Sichau were discontinued pursuant to Art. 205 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, because the suspect is unfit to be interviewed or appear in court. He suffers from […] angina pectoris, arterial hypertension and mild diabetes. According to the medical opinions issued on 2 September 1975 by the Grevenbroich district physician, on 8 December 1976 by Prof. L. Seipel, and on 5 July 1978 by Dr. Schnelbacher, the suspect Sichau cannot be interviewed without direct threat to life and health. The stress of an interrogation could at any moment cause an imminent danger of a heart attack or a stroke. For this reason, the proceedings have to be discontinued.

Decision of the Prosecutor’s Office in Düsseldorf on the discontinuation of proceedings against Heinrich Sichau

The quoted testimonies were given in the 1970s. The excerpts come from the materials gathered for the purposes of investigation “into the murder of a Polish citizen of a Jewish origin, Anna Kowalska, committed in Somianka by a German gendarme from the station in Wyszków, Heinrich Sichau” (IPN, OKŚZpNP Wa, S. 66/10/Zn).

The steadfast attitude of Anna Kowalska saved the lives of three helping Polish women - one of them was Marianna Stępkowska. Her daughter, Marianna Wacława Wojtkun, relates the tragic events of 1942.

The “Called by Name” program is dedicated to Poles and representatives of other nationalities who were murdered for helping Jews during the German occupation. The memory of those who showed heroism in the face of German terror is cherished in their families, yet these stories remain largely unknown to the general public. The program was created out of the need to mark the sites connected with the murdered victims in the public space. The Pilecki Institute strives to make these local experiences part of the universal historical awareness.

Source: Polish Press Agency