Lemkin. Witness to the Age of Genocide | exhibition - Instytut Pileckiego

09.12.2019 (Mon)

Lemkin. Witness to the Age of Genocide | exhibition - Instytut Pileckiego

The first exhibition in Poland to be devoted entirely to Rafał Lemkin

On 9 December 1948, the United Nations unanimously adopted the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. Thus, genocide was officially recognized as a crime under international law. Among those present in the Palace de Chaillot in Paris was the creator of the concept of “genocide” and the author of the draft of the Convention, Rafał Lemkin – a Polish lawyer of Jewish origin.

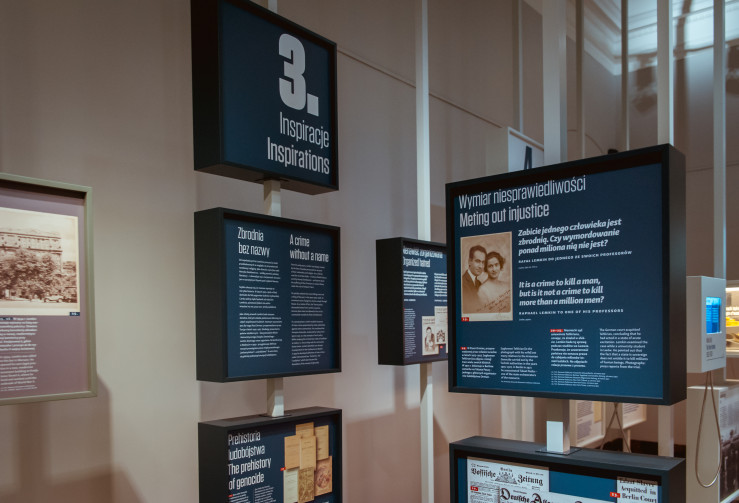

“Lemkin. Witness to the Age of Genocide” is the title of the first-ever exhibition in Poland, organized by the Pilecki Institute, to be devoted entirely to the person of Rafał Lemkin. Its opening coincided with the 70th anniversary of the adoption of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, which Lemkin considered as his life’s work. Warsaw, the city where he had had his legal practice and from which he fled before the advancing German forces in September 1939, suffered heavily from German crimes – the victims of which included both Jews and Poles – throughout the War, and this makes it a fitting location to speak about the life and achievements of Rafał Lemkin.

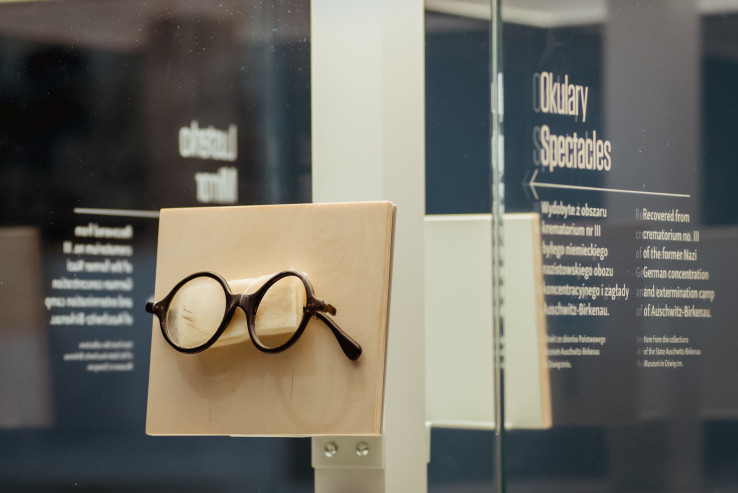

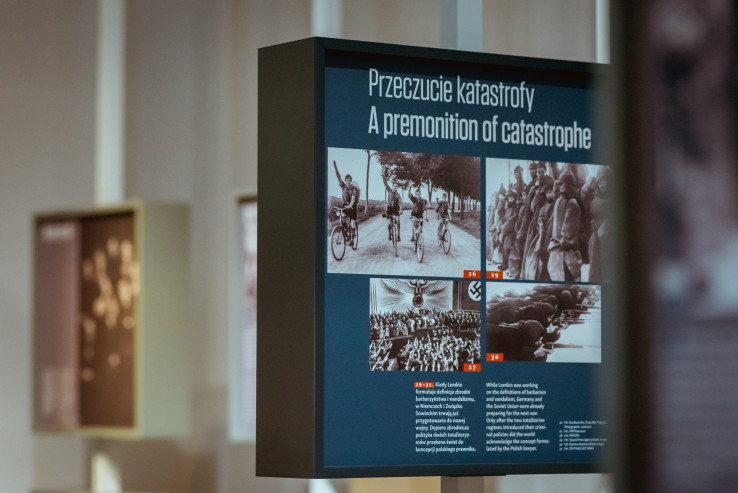

The exhibition utilizes photographs, documents, and audiovisual materials from American archives, the majority of which have not been hitherto presented in Poland. We tell the story of a man who was born in the Eastern Borderlands of Poland and went on to receive his education and work in the Second Polish Republic. Years later, he was forced to flee from the Nazi German terror and finally settled in the United States, where he created a concept that many now view as the most important response, formulated on the basis of law and political philosophy, to the tragic experience of the Second World War. The life and work of Lemkin – one of the heroes of the 20th century – has been presented against the tragic backdrop of the German and Soviet occupation of Poland and other countries of East-Central Europe, which became the site of the mass atrocities perpetrated by these two totalitarian regimes. In the exhibition, these acts of genocide have been illustrated by the accounts of survivors and given a very human dimension through the addition of personal items of the victims.

The concept of genocide is a direct reaction to totalitarian social engineering, and in particular to the Holocaust, in which Lemkin lost nearly his entire family. However, his concept would not have been developed if not for his previous experiences and observations. Henryk Sienkiewicz’s “Quo Vadis”, which he read in his early childhood; Russian anti-Semitism; press accounts of the Armenian Genocide; and, finally, his university studies in Lwów, a leading center of Polish legal thought and a city of symbolic significance for the old Commonwealth of Both Nations, which grouped together many ethnicities, religions and cultures – all these factors play an important role in the narrative of the exhibition. Without them it would be impossible to understand the concept which forms and will undoubtedly continue to form the fundamental legal barrier to systemic mass murder and other crimes against humanity. Recognizing the fact that people live and develop in distinct national, religious and social groups, it constitutes a voice of support for the right of human communities to peaceful coexistence. Together with universal human rights, this notion constitutes one of the foundations of international order. It is therefore not by chance that two key documents – the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights – were adopted by the UNO at the same session, just a day apart.

But the history of mass crimes targeting the existence of entire national and religious groups, of efforts aimed at punishing and preventing genocide, and of the struggle against its long and ominous shadow do not end with the Second World War and the adoption of the Convention of 1948. By mentioning the atrocities committed in Cambodia, Rwanda and the former Yugoslavia, our exhibition provokes a reflection on contemporary and future challenges: terrorism, neo-imperialism, biopolitics, and rapid technological development. Lemkin’s concept, which grew from the experience of global confrontation with the two leading totalitarian systems of the 20th century, is universal in its scope and application, and thus remains current irrespective of place and time. For years, the international community has used it as the basis for creating a system of punishing and preventing genocide – from the International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg to the International Criminal Court. The effectiveness of these actions and institutions continues to be the subject of animated discussion and dispute. The exhibition also considers the issue of abandoning the punishment of Communist crimes. Further, we recall the “Butcher of Warsaw”, Heinz Reinefarth, who after the War became mayor of the township of Westerland on the island of Sylt and was elected deputy to the Schleswig-Holstein Landtag. It is a fact that in many instances the crimes committed against citizens of the Second Polish Republic – Lemkin’s homeland – remain unpunished. The future of communities which fell victim to genocide continues to depend on their own approach to history, on whether by keeping their tragic experiences in memory they will be able to harness them as a foundation for building a successful future. The state of Israel, the “Solidarity” movement in Poland, and the Maydan in Kiev – all these are the positive results of such endeavors. Thus, they constitute the epilogue to our exhibition.

Raphael Lemkin, known first and foremost in scholarly circles and amongst experts in international law, deserves to be included amongst the key personages of the 20th century as an eminent intellectual, an authoritative researcher of totalitarian crime, and the author of the concept of genocide. Along with Jan Nowak-Jeziorański, Jan Karski, Witold Pilecki and Szmul Zygielbojm, he strove to make the world aware of the magnitude of the tragedy taking place on the Polish lands occupied by Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia. His concept received universal recognition, forever changing international law and the way in which humanity approaches the issue of intercommunity relations. These reasons alone are sufficient to substantiate our rediscovery of one of the most famous lawyers of the past century, truly a “witness to the age of genocide”.

Organiser: Pilecki Institute

Partners: Ministry of Culture and National Heritage; National Centre For Culture

photo: Grzegorz Karkoszka