KL Gusen - the forgotten camp | interview - Instytut Pileckiego

KL Gusen - the forgotten camp | interview

An interview with Rudolf Haunschmied who is a member of the Gusen Memorial Committee and a self-educated historian. Most of the commemorative initiatives for the KL Gusen concentration camps of the last decades were based on his activities and research.

When and under what circumstances did you learn that a concentration camp had operated in St. Georgen an der Gusen during the Second World War? What were your sources of information – were any publications on the subject readily available at the time?

I learned about the former concentration camp in St. Georgen when I was still a small child, less than 6 years of age. I remember one day when my father took me to the edge of the former “Mögle” sand pit at St. Georgen, where during the War inmates of KL Gusen II would be sent into the “Bergkristall” tunnels. This was around 1970. On that day I was fascinated by the trucks driving down in the sand pit, because from the distance they looked like toys. But I also got a first impression of the former “Bergkristall” tunnels – an impression that I never got out of my mind. From my early childhood I also remember that children in St. Georgen who were physically thin would be addressed by some of the older locals as “KZ-ler” (a term for concentration camp inmate).

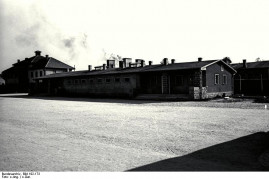

Later, while in primary school in St. Georgen, I was in two forms that had classes in the former SS kitchen barracks, which had been adapted by the local community for school purposes already in 1950. I remember the old, plain central heating radiators especially well, for some years later I stumbled upon some identical heaters near the former gas chamber in the KL Mauthausen Memorial. This was a key finding for me, and from that moment on I wanted to know whether there was any connection between KL Mauthausen and my classroom. Actually, this finding was possible only because my father had given my brother and me a comprehensive tour of the remnants of KL Mauthausen (showing us the quarry, the monuments, and the exhibition) when we were young. He was a teacher in the local secondary school and did this using a pedagogical approach suited to our age. So, he was my first source of information on my home region’s cruel past. There were no publications available at the time, and neither did we learn anything about this terrible period in school. When I asked anybody questions, the majority of local residents of St. Georgen would offer vague replies about “prisoners”, “aircraft”, or “Messerschmitt”, simply because they lacked more detailed background knowledge.

How did the local community respond to your efforts aimed at discovering the history of KL Gusen? Did your commitment to this cause meet with approval or was your inquisitiveness frowned upon? What challenges and problems do you face as a “guardian of memory” of this site of tragic suffering of so many nations, including Poles? How does the local community deal with the fact that the camp was built for the purpose of exterminating the Polish intelligentsia?

The people of St. Georgen or Langenstein didn’t talk about the horrors they had witnessed for decades after the War. Similarly to the survivors, they were traumatized, while the atmosphere just wasn’t ever right to speak about the crimes they’d seen committed in their neighborhoods during the conflict. In consequence, for years after 1945 St. Georgen was a town without a past. When I published my first chapter about the former KL Gusen concentration camps and the “Bergkristall” in 1989, having been requested by the market community of St. Georgen (Haunschmied, 1989, pp. 73–112), the editors and I were surprised by the immense interest of the local population in the topic. This was because there was practically no “official” information on that period of history for decades. To date, no one has criticized or censured me in person for researching the subject. Only some elderly men warned me and recommended to let things rest, saying “You’ll never understand what happened”. I think they did so because they were themselves somewhat traumatized and never saw the bigger picture of what had really happened between 1938 and 1945 in their home region, and why. So I was the first who started to analyze this bigger picture, and I must say that it is clear to me that much more can still be learned about the KL Gusen complex even after 30-plus years of continuous, intense and sincere research conducted on a global scale.

To date, the biggest challenge is that most of the archival materials concerning the KL Gusen complex are available in foreign languages and are scattered all around the world. Thus, the challenge is to locate this material, bring it to Austria, to translate it, and finally to subject it to detailed study. Poland is the most important country in this regard, for nowhere else have so many books and articles been published on the topic. Furthermore, Polish archives contain plenty of materials concerning Gusen – but, unfortunately for me, the majority have been written in Polish, and I simply can’t afford to travel so many times to Poland to evaluate these texts and have them translated. Incidentally, I feel obliged to add that I learned most of the wartime history of my home region from sources outside Austria – especially those originating from Poland and the United States.

The fact that KL Gusen I was erected in tandem with the German invasion of Poland as a death camp for the extermination of a significant part of the Polish intelligentsia was not really known to most local inhabitants. The only thing which they observed was that in 1940 KL Gusen I was overcrowded with male inmates from Poland, and that these prisoners were treated very brutally or even shot while working outside the camp on the construction of the DEST administrative buildings, the SS rifle range, nearby roads, or on the SS railway line. Consequently, contemporary locals called KL Gusen I the “Polenlager” (the “camp for Poles”). Unfortunately, the SS successfully spread a rumor among the townsfolk that all these Poles were “criminals” who deserved such ill treatment, and it therefore took some time for people to learn that they were in fact teachers, professors, priests, politicians, artists and other representatives of the Polish intelligentsia. Today all local residents know that the majority of those incarcerated at the KL Gusen complex were not “criminals” but innocent people – patriots who had actively opposed the Nazi aggression against their countries.

What was the most heartrending, incredible, or simply most surprising experience in the course of your research? In short, what made the greatest impression on you?

The most heartrending experience occurred in the 1990s, when I and my colleagues from the Gusen Memorial Committee (www.gusen.org) had the privilege of establishing closer contacts with the survivors of KL Gusen, who started sharing their knowledge with us, the young Austrians. This was very important for me and my friends, because until then we knew nothing from the very personal experience of the survivors. Previously there was no direct contact between members of the local population and the survivors who came to Gusen regularly from many different countries. They were simply considered as “strangers”. From my early childhood on, I remember especially the groups of Polish survivors who came over during the Communist period; they had to camp out in their coaches in the open fields around St. Georgen because staying in a hostel was too expensive for them. There was also the language barrier and – maybe – some “tour guides” prevented any contact between them and interested “foreign” guys like me. It was also heartrending for me that some Polish survivors requested food at the St. Georgen municipality and Roman Catholic parish in the early 1980s, when Poland and especially its retirees suffered a deep economic crisis during the Jaruzelski regime. These requests, driven by pure hunger, were definitely the first contacts I had with Polish survivors, and indeed my family sent food to some of them over a period of several years. Looking back at the last 35 years of involvement and research, I must say that the growing partnership and friendship with so many victims and their families from all around the world – and especially from Poland – was and continues to be my most heartrending experience, and at the same time the best compensation for the thousands of hours of my spare time that I’ve dedicated to them, to researching the KL Gusen complex, and to ensuring the remembrance of its victims.

What still remains to be discovered about the history of KL Gusen? What are the biggest question marks at the moment? Or maybe at this point some facts can no longer be determined or uncovered?

Although I and my colleagues have learned a lot about the hitherto unknown history of the KL Gusen I, II& III complex in the last decades, it is clear that many aspects require much broader and more in-depth research in the future. In this regard, the following would be the key issues:

■ The translation of the many Polish books written on the subject of the former KL Gusen complex into German. Otherwise, the Austrians (and Germans!) will never learn what “Gusen” and its huge war industries really were.

■ The provision of access to and transfer of additional archival materials (and this concerns Poland in particular) concerning the KL Gusen camps to active Austrian researchers like myself for study, and also in order to make these sources available to other researchers and students both in Austria and elsewhere.

■ The opening up of the holdings of Russian archives concerning the KL Gusen complex, including those pertaining to the underground “Kellerbau” and “Bergkristall” plants, and the operation of the KL Gusen granite quarries and the DEST installations in St. Georgen under Soviet administration until 1955.

■ The sale of German items of property related to KL Gusen by the State of Austria in the years 1955–1964.

■ Conducting more detailed research on the extermination of Jews (from Hungary, Poland, Romania and Greece) and the fighters of the Warsaw Uprising, especially at KL Gusen II in 1944 and 1945.

■ Establishing the link between KL Auschwitz-Birkenau and KL Gusen II, an element of which was the selection and partially direct transferal of Jews to work on the construction of the huge underground installations at St. Georgen.

■ The reason for the operation of an external KL Gusen command at Gaisbach in 1944/45 (approx. 15 km from St. Georgen an der Gusen or Lungitz) – was this the beginning of yet another camp, Gusen IV?

■ The possible reason for the radioactive contamination of the “Bergkristall” tunnels at St. Georgen, because the nearby sister tunnels of “Kellerbau” appear to be clean.

■ The background as to why very likely already in September 1942 (!) a command of the German Air Force was established at St. Georgen in connection with the construction of the monstrous underground plant that later came to be known as “Bergkristall”.

■ The whereabouts of several hundred railway cars of machinery that were brought by the company Steyr-Daimler-Puch in the autumn of 1944 from Polish plants in Warsaw and Radom to the SS facilities in Gusen.

You were joined in your research on the history of KL Gusen by your teacher, Mrs. Martha Gammer. How did your cooperation begin? Could you name any other persons who made a particularly valuable contribution to uncovering the history of KL Gusen?

At first let me point out that Mrs. Gammer was not really my teacher. She taught at the secondary school which I attended, and I only had some lessons with her – in German and geography – when for a few weeks in the late 1970s she stood in for my form teacher in these subjects. My cooperation with Martha Gammer on the topic of KL Gusen started with the foundation of the “Arbeitskreis für Heimat-, Denkmal- und Geschichtspflege St. Georgen an der Gusen” in 1985/86, for we were both founding members of this regional historical association which over the years evolved into the Gusen Memorial Committee (www.gusen.org). Our collaboration deepened in 1988/89, when the two of us were asked to contribute to a history book on the community of St. Georgen (300 Jahre, 1989). I myself authored a pioneering chapter devoted to the former St. Georgen-Gusen complex, while Mrs. Gammer – being a German teacher – proofread my writing. This publication, and my chapter in particular, were subsequently presented during an official community evening in 1989, arousing immense interest on the subject among local residents. From this moment on, Martha and I worked as a team, devoting our efforts to researching and promoting the by then already lost history of the KL Gusen complex in Austria and abroad.

This publication, focused on the “lost history” of the region, was made possible by two members of the communal council of St. Georgen who took political responsibility already in 1988/89. They were Mr. Rudolf Lehner Jr, the young Head of the Municipal Committee for Cultural Affairs, and Mr. Johann Hackl, who was mayor at the time. I should also mention Mrs. Andrea Wahl, who was in charge of the local Education Center for adults. In the early 1990s, she encouraged me to offer regular guided tours and hold study groups for people interested in the topic. And last but not least, my colleagues and I would like to thank Mr. Pierre Serge Choumoff of Paris, France, for his willingness to share his immense knowledge of the KL Gusen camps and his help in establishing contacts with survivors all over the world. A survivor of KL Gusen I, he was the Vice-President of the Amicale Francaise de Mauthausen and of the International Mauthausen Committee. He first contacted me in 1993, requesting that I help him organize the first joint commemoration of local residents and survivors at the Gusen Memorial, which was to be held in 1995.

The literature of the subject distinguishes Gusen I, Gusen II and Gusen III. Could you outline the differences between these three camps?

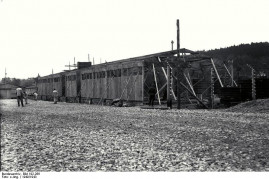

KL Gusen I was actually the twin of KL Mauthausen, and equaled it in size. From the beginning, both concentration camps were planned to form a system with a common economic administration at St. Georgen. And just like in Mauthausen, the use of forced labor in Gusen commenced already in the autumn of 1938, with the first workers coming from a makeshift camp in the Wienergraben valley. In 1939 the SS invested such large amounts of money in setting up its largest and most modern granite quarry in Gusen that it could only afford to establish its second concentration camp at the location only at the time of the German invasion of Poland. Thus, the opening of KL Gusen I is linked directly with the start of hostilities against Poland in September 1939; in 1940, when the camp became fully operational, it already had as many as 8,000 Poles. Hundreds of the inmates died after only a few months of incarceration. Soon, the initial “Polenlager” in Gusen became a death camp for prisoners of other nationalities, too: Spaniards, Soviet POWs, Germans, Austrians, etc. In 1942/43, most of the slave labor was shifted to war production, and KL Gusen I, which had a direct railway connection with St. Georgen, became an important industrial facility of the SS. In 1943 the SS started work on the design and construction of its first underground plant at Gusen, the “Kellerbau”, using among others the expertise of highly qualified Polish engineers who were imprisoned at the camp.

Since the conditions there were excellent from the point of view of industrial production, with the facility being managed almost directly by the regional DEST administration in St. Georgen, at the turn of 1944 the decision was taken to use it as the location for one of the biggest and most modern underground plants of Nazi Germany, codenamed “Bergkristall”. Further, in order to double the capacity of KL Gusen I it was resolved to convert the already existing clothing warehouses for SStroops at Gusen into a second but much more primitive concentration camp; this would come to be known as KL Gusen II, and it was initially populated with thousands of Jews selected from KL Auschwitz-Birkenau. This camp served as a labor pool and rapidly came to be recognized as the most evil element of the entire KL Mauthausen-Gusen complex and, indeed, as one of the cruelest such facilities in Nazi Germany. When the first batches of Jews had been murdered, hundreds of Poles captured during the Warsaw Uprising were deported to this “Hell of Hells” in the autumn of 1944 – soon, they met the fate of their predecessors.

Since the first sections of the “Bergkristall” underground plant were commissioned in early autumn 1944, a third but smaller concentration camp – KL Gusen III– was opened in the village of Lungitz, just a few kilometers north of St. Georgen, with direct railway access to “Bergkristall” and KL Gusen I and II. KL Gusen III was used to house about 300 forced laborers who worked in a Messerschmitt warehouse which served the Messerschmitt plants in St. Georgen and Gusen, and also in a makeshift bakery that made bread for the inmates of the by then immense St. Georgen-Gusen-Mauthausen complex of concentration camps.

During a conference organized by the Pilecki Institute (formerly Witold Pilecki Center for Totalitarian Studies) in May 2017, participants discussed a project for establishing the Henryk Sławik European Center of Education, which would be built on the former camp grounds. What do you think about this idea? What, in your opinion, is the greatest value of joint initiatives in the field of the culture of memory?

The idea to turn the still existing SS barracks in Gusen into a European Center of Education that would be named after Henryk Sławik is excellent, and I really do hope that it will come to fruition soon. The amazing thing about this project is that it would serve to underscore the intellectual and professional potential of those who were imprisoned in KL Gusen, especially through the names and topics of the seminars that would be organized there, and never allow us to forget their fates – tragic to a greater or lesser degree, but tragic nonetheless. We would therefore do well to heed this terrible lesson and keep in mind the fact that by their crimes the Nazis severely stunted the scientific, political and cultural development of postwar Europe.

In my opinion, the greatest value of joint initiatives in the field of the culture of memory – and the KL Gusen complex, the epitomization of evil, is a prime example in this regard – is that both local residents and visitors from the world over learn just how menacing and deadly human beings can become to others of their species, and that values like human dignity, human rights and solidarity are key to ensuring the humanity and fairness of civilization. Also, the history of the site can be used to demonstrate, study and teach how people behave in extreme situations.

Does the history of KL Gusen spark considerable interest among Austrian historians? Do Austrian researchers willingly take up this subject? What is the approach of the authorities – both the local government in St. Georgen an der Gusen and the central authorities in Vienna?

No, in my opinion there is a lack of interest in (and no great awareness of) the former KL Gusen complex among historians, either in Austria or the numerous other nations associated with the history of the camp. I think this is primarily due to the fact that two very different historical locations, Gusen and Mauthausen, are regularly mixed up, and that this error of confusion is then compounded by the fact that both sites used a common administration and infrastructure situated in St. Georgen. Indeed, the higher SS commands in Munich (and later on in Berlin) subsumed these three different locations under the term “Mauthausen” from practically the beginning. These vagaries of nomenclature have misled generations of researchers right up to the present day, frequently causing them to lose sight of the places where atrocities really occurred. For example, the headquarters of the so-called “Granitwerke Mauthausen” (the regional DEST granite works), which administered and made available slave labor from the concentration camps of Gusen and Mauthausen, were actually located in St. Georgen from 1940 and had nothing in common as regards topography with the community area of Mauthausen. Therefore it is clear to me that when seeing the name “Mauthausen” in documents, historians with an insufficient knowledge of the region were being misled as to the actual locations of the camps. Put simply, it is my stated opinion that the extermination sites of Gusen were being successfully “camouflaged” by the Mauthausen “brand” already during the war years, and in the main continue to remain hidden. Over the years, only Polish survivors took care to add the important but regularly omitted word “Gusen”, thus ensuring that the system of concentration camps was and remains known as Mauthausen-Gusen.

As I’ve pointed out above, a proper approach to the St. Georgen-Gusen-Mauthausen complex must be based on a comprehensive know-ledge of the region. Thus, over the past 35 years we have worked to develop a highly constructive approach with the participation of the local authorities and communities of St. Georgen an der Gusen and Langenstein; indeed, most of the goals we’ve achieved were significantly facilitated by their good will. But the further we move away from St. Georgen an der Gusen or Langenstein, the more we see that national-level authorities – like the provincial government in Linz or government officials in Vienna – have still not learned what the real significance of the KL Gusen complex is. Last year, for example, when one of the best books ever to be written on the subject of KL Gusen II (Fisher, 2017) was being presented at the Mauthausen Memorial, the former Governor of Upper Austria did not even once use the name “Gusen” in his address. Apparently for him, the locations of terror and extermination at St. Georgen and Gusen, as well as their victims, are not worthy of mention. How could such political leaders be able to provide the necessary support for projects that are developed by local or foreign individuals or organizations? The litmus test of the sufficiency of knowledge and awareness on the part of the Austrian state authorities and politicians will be their decision whether to purchase the currently available plots of KL Gusen I, which include the two SS barracks needed for the proposed European Henryk Sławik Center of Education, the roll-call square with its impressive granite walls, and the remnants of the stone crusher, by the end of 2018. We will see whether the Austrian government will take this opportunity to redress the serious material damage inflicted by the Soviet administration in the years 1945–1955, and rekindle the collective memory of this largest and most barbaric Nazi concentration camp complex to be established in Austria, which destroyed more human beings than the nearby twin structure at Mauthausen.

In 2016, there was an uproar in the media after bulldozers were driven into the former roll-call square of KL Gusen. Two years later, can we be sure that this will never be repeated?

No, we can’t be sure. It will all depend on the decision that the Austrian government will make in the next few months as regards the repurchase of this property by the state, and whether it displays the political will and honesty to dedicate the lands once occupied by the largest concentration camp in the history of Austria to the memory of its more than 70,000 former prisoners.

The interview has been published in Totalitarian and 20th Century Studies Vol. 2 (Pilecki Institute, 2018).

Rudolf A. Haunschmied was born in 1966 in St. Georgen an der Gusen, Austria. He has been studying the history of the Gusen I, II& III concentration camp complex since his early youth, while at the same time gaining an education and taking up work as a mechanical engineer. For decades, he has been campaigning for the inclusion, protection and preservation of the remnants of KL Gusen within a St. Georgen-Gusen-Mauthausen memorial area. He is also an initiator and promoter of the new Mauthausen-Gusen-St. Georgen Region of Awareness that came into being towards the end of 2016.

See also

- Research paper of an employee of the Pilecki Institute in a Q1-indexed journal

News

Research paper of an employee of the Pilecki Institute in a Q1-indexed journal

Dr. Tomasz Chinciński published an article in the Q1 journal Cogent Arts & Humanities on the attitudes of the German population in Poland incorporated into the Third Reich.

- Inauguration of the Pilecki Institute in New York | A transatlantic bridge for values that are dear to us all

News

Inauguration of the Pilecki Institute in New York | A transatlantic bridge for values that are dear to us all

This coming weekend, the Pilecki Institute will inaugurate its activities in New York.

- Debate: Lessons from Nuremberg for the 21st Century | Inauguration of the Pilecki Institute in New York

News

Debate: Lessons from Nuremberg for the 21st Century | Inauguration of the Pilecki Institute in New York

During the debate we will look at how the Nuremberg Trials and the structures of international justice and cooperation between states that they initiated helped shape the post-war world order.

- "Germans Appropriate the Polish Experience of Victimhood. Colonial patterns of thinking emerge in the debate on collaboration" by Hanna Radziejowska and Mateusz Fałkowski

News

"Germans Appropriate the Polish Experience of Victimhood. Colonial patterns of thinking emerge in the debate on collaboration" by Hanna Radziejowska and Mateusz Fałkowski

Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, March 11, 2026. Article translated from German into English.

- Competition for the position of Adjunct in the Humanities, Department for the study of Nazism and German occupation during the Second World War

News

Competition for the position of Adjunct in the Humanities, Department for the study of Nazism and German occupation during the Second World War

We invite you to participate in the competition for the position of Adjunct in the Humanities, Department for the study of Nazism and German occupation during the Second World War.

- Courtroom 600. Witnesses of Nuremberg

News

Courtroom 600. Witnesses of Nuremberg

Eighty years after the beginning of the landmark Nuremberg Trials (November 1945), a documentary audio series “Courtroom 600. Witnesses of Nuremberg” restores the voices of those who stood on the margins of great history.

- PORTRAITS | Adam Bałdych Quintet

News

PORTRAITS | Adam Bałdych Quintet

“Portraits” is a moving story told through sound, in which jazz meets history and individual fates intertwine with the collective experience.

- Competition for the position of Adjunct in the Humanities

News

Competition for the position of Adjunct in the Humanities

Competition for the position of Adjunct in the Humanities, Department for the study of Nazism and German occupation during the Second World War at the Witold Pilecki Institute of Solidarity and Valor.

- Merry Christmas!

News

Merry Christmas!

On the occasion of Christmas, we wish you all the best and every success in 2026.

- The Lemkin Laboratory – the Pilecki Institute and the Mieroszewski Centre sign cooperation agreement

News

The Lemkin Laboratory – the Pilecki Institute and the Mieroszewski Centre sign cooperation agreement

- 2025 | Michał Bilewicz, „Traumaland. Polacy w cieniu przeszłości"

News

2025 | Michał Bilewicz, „Traumaland. Polacy w cieniu przeszłości"

Michał Bilewicz’s “Traumaland. Polacy w cieniu przeszłości” (Wydawnictwo MANDO/Wydawnictwo WAM) won the Witold Pilecki International Book Award in the “academic history book” category.

- 2025 | Emil Marat „Bratny. Hamlet rozstrzelany"

News

2025 | Emil Marat „Bratny. Hamlet rozstrzelany"

The book “Bratny. Hamlet rozstrzelany” (Wydawnictwo Czarne) won the Witold Pilecki International Book Award in the “historical reportage” category.