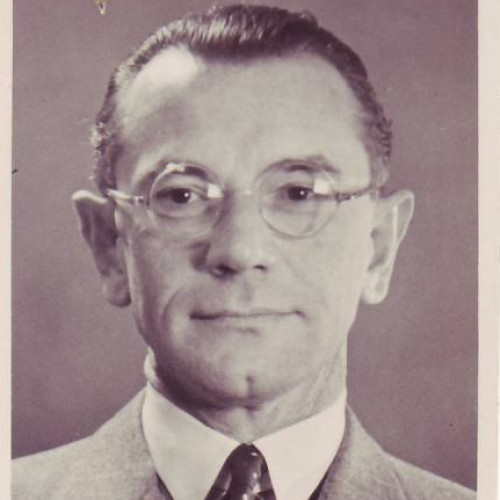

Semen Biliczuk - Instytut Pileckiego

Jews, Ukrainians, Poles – the population of the prewar village of Kisielin [now Kysylyn] [now Kysylyn] was characterized by a vivid mosaic of ethnic and religious groups. The leader of such a community had to be able to find a common ground with everyone.

But apart from being the village head, Semen Bilichuk was also a father, and he attached great importance to this role: at the age of twenty, he had married Kateryna, with whom he had three daughters – Ahrypina, Iryna and Valentyna.

The Bilichuks lived in close proximity to the family of Antoni Sławiński. On Sunday, 11 July 1943, members of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (faction of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists) attacked the Poles gathered for Holy Mass at the church in Kisielin. The attack resulted in the deaths of approximately 90 people.

Four days later, Semen provided shelter to the Sławiński family, hiding them in the barn. The Banderites found out and came to the Bilichuks’ house, demanding to speak with Antoni. Here’s how Antoni’s daughter, Aniela Dębska, recalled this conversation later:

“they said that we didn’t have to run and we had nothing to fear, and that they were going home… Later on, after the soldiers went away, Bilichuk came to the barn. He told my father: ‘don’t listen to them, grab whatever you can and leave, because there’s no more life for you here.”

Semen’s words convinced the Sławińskis to leave Kisielin, which saved them from sharing the fate of their compatriots who were murdered by the Banderites. A year later, when the Red Army was advancing towards the settlement, the Bilichuks left for the village of Studynie and returned to Kisielin only after it seemed safe to do so. However, when Semen entered the house, the building exploded – Red Army soldiers had most likely mined it before continuing their westward march. Semen died instantly. His family remained in Kisielin.

“On that Thursday, when my husband was taken by cart to the hospital, we

spent the night in Bilichuk’s barn. Bilichuk came to the barn and invited my

father to the house. He said that some armed men, partisans, wanted to

speak to him. My father went there and we stayed put. When he returned,

he told us that they said we didn’t have to run, we had nothing to fear and

should return home... Later on, after the soldiers went away, Bilichuk came

to the barn. He told my father: ‘don’t listen to them, grab whatever you can

and leave, because there’s no life for you here anymore.’”

Account of Aniela Dębska from the 2003 film Oczyszczenie, directed by Agnieszka Arnold.

See also

- gen. Lóránd Utassy (1897— 1974)

awarded

gen. Lóránd Utassy (1897— 1974)

Utassy denied the Gestapo access to the internment camps and refused to surrender Polish soldiers. He also participated in talks with the Red Cross, aiming to establish it as the representation of Poles who had found themselves on Hungarian soil.

- Mychajło Susła

awarded

Mychajło Susła

(1901–1970)A double Christmas, a double Easter: Roman Catholic and Greek Catholic. This is how Irena Próchniak remembers the celebrations in Podkamień in eastern Galicia.

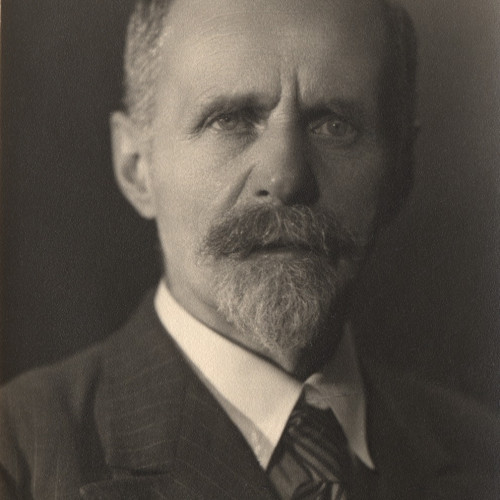

- prof. Władysław Konopczyński (1880—1952)

awarded

prof. Władysław Konopczyński (1880—1952)

After the Warsaw Uprising, among the crowds expelled from the burning city were the family of a Polish-Jewish historian, Ludwik Widerszal. Konopczyński offered shelter in Młynik until the end of the war.